“I didn’t know what the term ‘freight forwarder’ meant until a year into starting the business.” Considering his shipping logistics startup Flexport was last valued at $3.2 billion, that quote from my first interview with CEO and founder Ryan Petersen back in 2016 seems even more surprising now.

But it also hints at why he’s one of the most talented and exciting executives in tech: He learns. Humbly. Relentlessly. About whatever the role requires as it evolves.

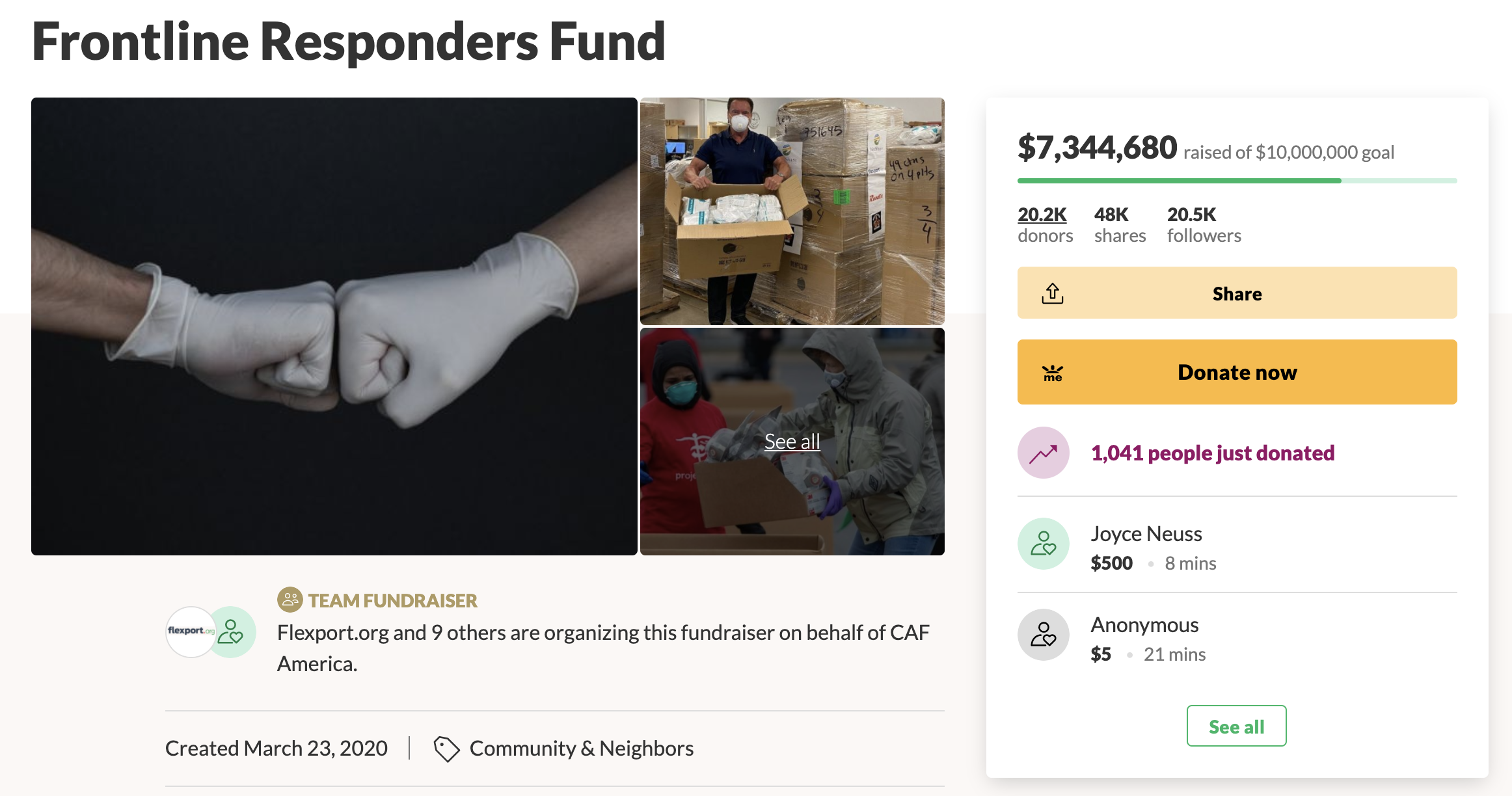

Right now, it means learning that 1.15 million medical masks can fit in a pasenger plane if you strap boxes to the seats like they’re people. Flexport has delivered around 62 million pieces of personal protective equipment, with delivery of over 7.7 million of those funded by the company’s non-profit arm Flexport.org. Petersen and Flexport meanwhile helped create the Frontline Responders Fund that’s raised over $7 million for COVID relief.

Flexport.org packed 3 million pieces of PPE into a repurposed passenger plane to get them to frontline responders

“He’s one of the most impressive founders I’ve known” said fellow FRF leader and Science co-founder Peter Pham. “Ryan just wants to solve problems without ego.”

In this profile, TechCrunch charts Petersen’s growth across our six interviews with him over the past four years as he raised $1.3 billion and reached hundreds of millions in revenue.

Overcoming Shlep Blindness

Petersen soon found out that ‘freight forwarding’ means coordinating all the shipping and hand-offs to get pallets and containers of goods on one side of the world, through trucks and boats and planes, to a retailer on the other. By then Flexport was going through Y Combinator in 2014, preparing to take on the trillion-dollar freight industry.

Ryan Petersen

“I thought the problem was too big, and that I wouldn’t be able to solve it” he recalls. “How am I going to fix global trade? Only much later did I realize that, well, let’s try it! It can’t just sit there broken forever.” Somehow, freight forwarding was still being organized with faxed logs and paper manifests, or Excel files and email if a client was lucky.

Freight forwarding had plagued plenty of founders but none had tackled it because it seemed so insurmountable that it engendered ‘schlep blindness’, as YC’s co-creator Paul Graham termed it.

“Schlep blindness is something so hard that your brain won’t think about it. I think it’s a necessary feature of our brains. Otherwise we’d sit here contemplating our mortality all day and never be able to do anything” Petersen explains. “Anyone who ever sold anything on the internet pre-Stripe went through this terrible process. 100% of internet entrepreneurs saw that problem and then went about their way.” With its 100 year-old shipping incumbents and endless regulatory acronyms, who’d want to wade in?

“Ryan is what I call an armor-piercing shell: a founder who keeps going through obstacles that would make other people give up” says Graham, who donated $1 million to Flexport.org’s COVID-19 relief efforts. “But he’s not just determined. He sees things other people don’t see. The freight business is both huge and very backward, and yet who of all the thousands of people starting startups noticed?”

Petersen. What really irked him was that the big freight forwarders didn’t want those clients to learn what influenced prices and timelines to keep them in the dark about how sub-optimal their routes were. “They just made money off the fact that I didn’t understand how it all works. And I assumed at the time that that was just something about entrepreneurs who are new to this space but it turns out even the biggest companies struggle with this stuff. They’re afraid forwarders are trying to take advantage of them.”

But Petersen wasn’t so naive. He’d actually been in the freight business his whole life.

From Slinging Soda To Founding Startups

“Maybe without her realizing it, she was training us to be entrepreneurs” Petersen reflects. He and he brother David grew up with a biochemist mom who ran her own food safety business while their dad did the company’s programming. “All of our childhood conversations were around using software to make government regulations more accessible.” When would Flexport would eventually be jumping through the hoops of the 43 different US trade regulators, it felt natural for its CEO.

Ryan Petersen back in 2015 before Flexport had its own planes

Petersen exudes a kinetic energy that subtly coveys that he’s always itching for the next knot to unwind. “At the time I was terribly bored by everything”. So his Mom put him to work. “She paid my allowance as a kid by having me deliver sodas to stock their office. My dad would drive me to Safeway to buy sodas for four bucks a case and sell them for nine.” With a laugh, he considers, “It was potentially a way for her to make my allowance tax-free.”

Soon Petersen was moving bigger items longer distances, buying scooters in China and selling them online in the States. By 2005, Petersen was living in China to get closer to the supply chains. The next year, he co-founded ImportGenius with his brother and Michael Klanko. They’d realized there was a ton of valuable information locked up in paper shipping manifests, so they began scanning and selling the data to importers and exporters so they could keep tabs on competitors.

Petersen’s first moment in the spotlight came in 2008 when he accidentally butted heads with Steve Jobs. ImportGenius had identified that Apple was shipping a large number of “electronic computers”, a new classification for the company. “We scooped the launch of the iPhone 3G with our public manifest data. Steve Jobs called US Customs, who called me” he told me back in 2016.

Though ImportGenius eventually plateaued, Petersen had accumulated the knowledge to lift the veil and pierce his schlep blindness. “I realized the largest problem was staring me in the face. Global trade is too hard, and there’s not software to manage it” he remembers. “I thought there was no software for SMBs. What I discovered was that there’s NO software.”

At first he wanted to build what would become Flexport inside of ImportGenius, but it was tough to get existing investors to stomach the risk. It’d be scary, but also exciting to start something separate. “My brother is my best friend and my best advisor” Petersen tells me. They’d always pushed each other with a jovial sense of competition — Ryan’s Twitter handle is @TypesFast. David’s is @TypesFaster.

So David made the first move, founding BuildZoom, which has gone on to raise $23 million to coordinate the logistics (are you sensing a pattern?) of hiring contruction contractors. In 2013, Ryan lept. “I think part of me wanted to go out on my own and prove myself . . . to prove that I was capable of running the show. It was a really, really challenging to do it. Then the day I did it, it was the most liberating, awesome feeling ever.”

They Laugh At You, Then You Raise $1 Billion

It took a few years to get all its regulatory approvals and develop the basis of the Flexport product. But with early capital from Founders Fund, Petersen built the freight software he’d spent so long pining for. Still, “Senior execs at big companies were making fun of us. One of them compared us to Doc Emett Brown [from Back To The Future] and his ‘flex capacitor’ but we he missed is that Doc invented a time machine and it worked.”

By 2016, Flexport was serving 700 clients across 64 countries. I described it as the unsexiest trillion-dollar startup, attacking an enormous industry that was so boring that it repelled earlier innovation. Oversaturation in consumer startup verticals was pushing investors to look to where tech was evolving previously untouched markets. Flexport raised a high-profile $110 million round led by DST at a $910 million post-money valuation in 2017, and Silicon Valley was starting to take notice.

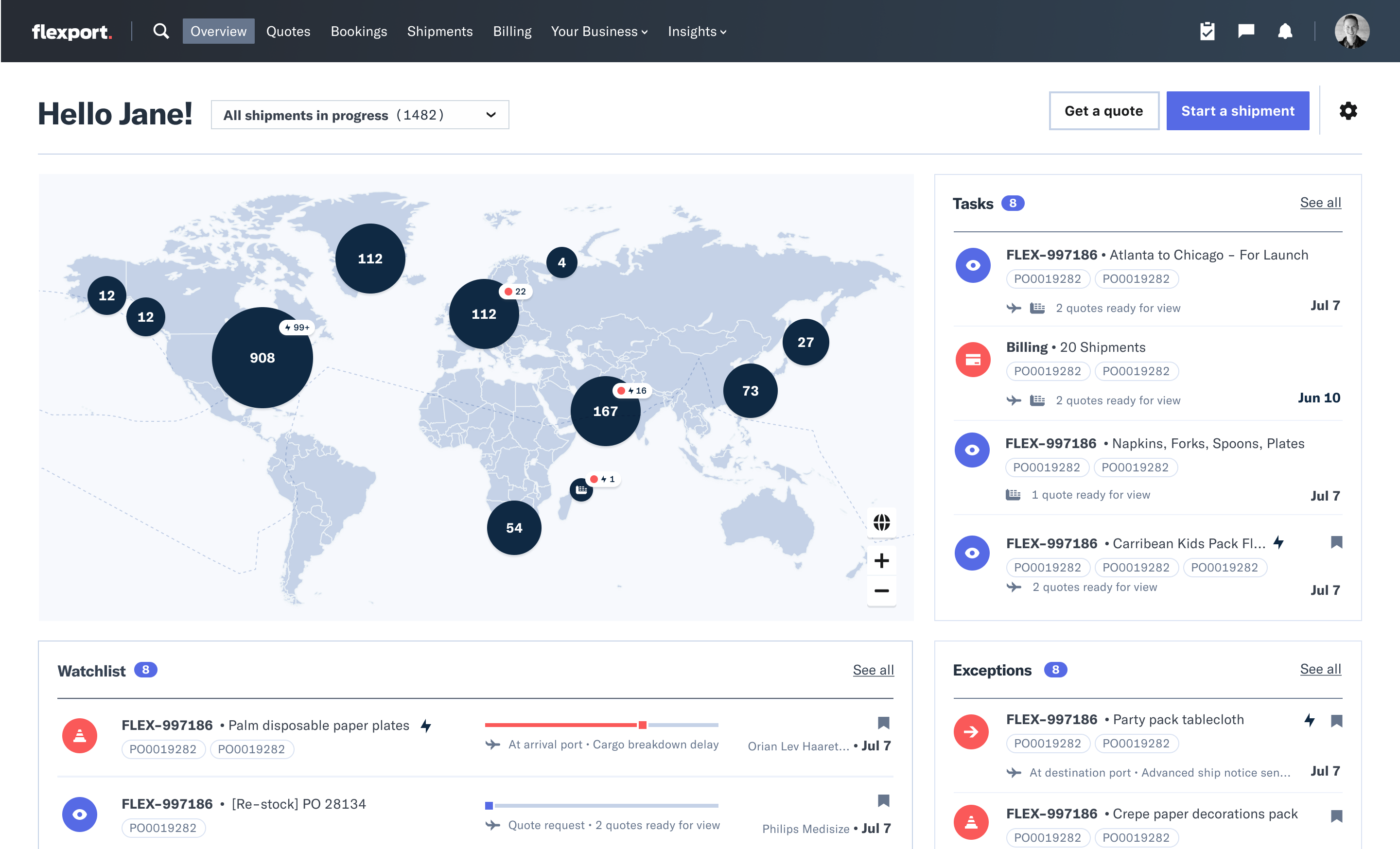

The Flexboard Platform dashboard offers maps, notifications, task lists, and chat for Flexport clients and their factory suppliers.

Luckily, the freight big-wigs were still laughing despite Flexport moving 7000 shipping containers per month for 1800 customers. “I don’t worry about startup competitors. I worry the big guys will stop thinking of us as such a joke” Petersen said that year. Soon incumbents like 25-year-old Chinese private delivery giant S.F. Express were allying with Flexport, leading another $100 million round in 2018. Meanwhile, Flexport was trying to sound more like its older competition. Petersen told me “We’re trying to retire the word ‘startup’. [Our clients] want a company that will help them grow, not the fly-by-night startup.”

At that point, Petersen didn’t care if freight was appealing or not. “I never thought it was sexy or unsexy. I just thought it was a backstage pass to the world economy” he’d later say. Yet SoftBank’s Saudi-backed Vision Fund felt the attraction. Flexport was vertically integrating, adding freight financing so retailers could pay factories for good they’d sell months later. It was also chartering its own plane and building its own warehouses where it could experiment with next-generation logistics, scanning the physical dimensions of everything that came through its doors to optimize future shipments.

By then, Flexport had plenty of exit options. But Petersen was enjoying the ride. “I’m just having fun. You have a purpose. You get invited to interesting things. Once you sell your business, you’re just another rich guy. I never want to sell the business.” Luckily, the potential to grab more of the freight forwarding profits convinced SoftBank to invest a jaw-dropping $1 billion into Flexport in early 2019 at a $3.2 billion post-money valuation.

“It was controversial with our board. They thought it was a lot of dilution to take on but I convinced them that, this was going to go up and down and we wanted we to have cash to ride out the cycles. My view is that the world’s uncertain. You should be prepared for all outcomes” Ryan explains. As long as it could weather the storm, “we’re going to win on some time horizon.”

That strategy soon paid off. When trade with China effectively halted as COVID-19 exploded in the country and Flexport had far fewer containers to coordinate, it didn’t have to execute mass layoffs like fellow late-stage startups. It proactively cut 3% of its staff or around 50 people on February 4th, centered in recruiting that it plans to slow. “It’s painful to disappoint people” Petersen reveals.

Flexport chartered its own plane for several years to ship freight

Transitioning to a recession-era CEO and learning to reduce headcount with empathy became Petersen’s new objective. “I wanted people to know that I take personal responsibility for it. I wanted people to know that there’s transparency here” he tells me, his voice straining under the gravity of the situation. “If people feel fear and then they look at the leadership and they think the leadership is not feeling fear, then the fear amplifies. Whereas if people feel fear and they see, ‘oh the leaders are feeling fear also? Then okay, they’re going to behave appropriately.'”

Taking decisive action before COVID-19 spread widely stateside kept Flexport’s momentum strong and its runway long. Petersen is proving he can guide the company through bust as well as boom.

Flexport’s Tricks To Management

“My big learning in the last 18 months or so is that you can’t do everything. You can do anything you want, but you can’t do everything” Petersen outlines. “I see good ideas and I say ‘DO THAT!'” he tells me with a wry smile. “Soon, you’re spread pretty thin. You need some top down discipline to say ‘no’ to things. We really lacked that in the early years.”

The quest for discipline led him to develop and lean on two major frameworks for prioritizing customer needs and preserving company culture. They’re crucial now that Flexport has grown to 1800 employees across 14 offices and 6 warehouses, and 10,000 clients including Sonos, Kleen Kanteen, and Timbuk2.

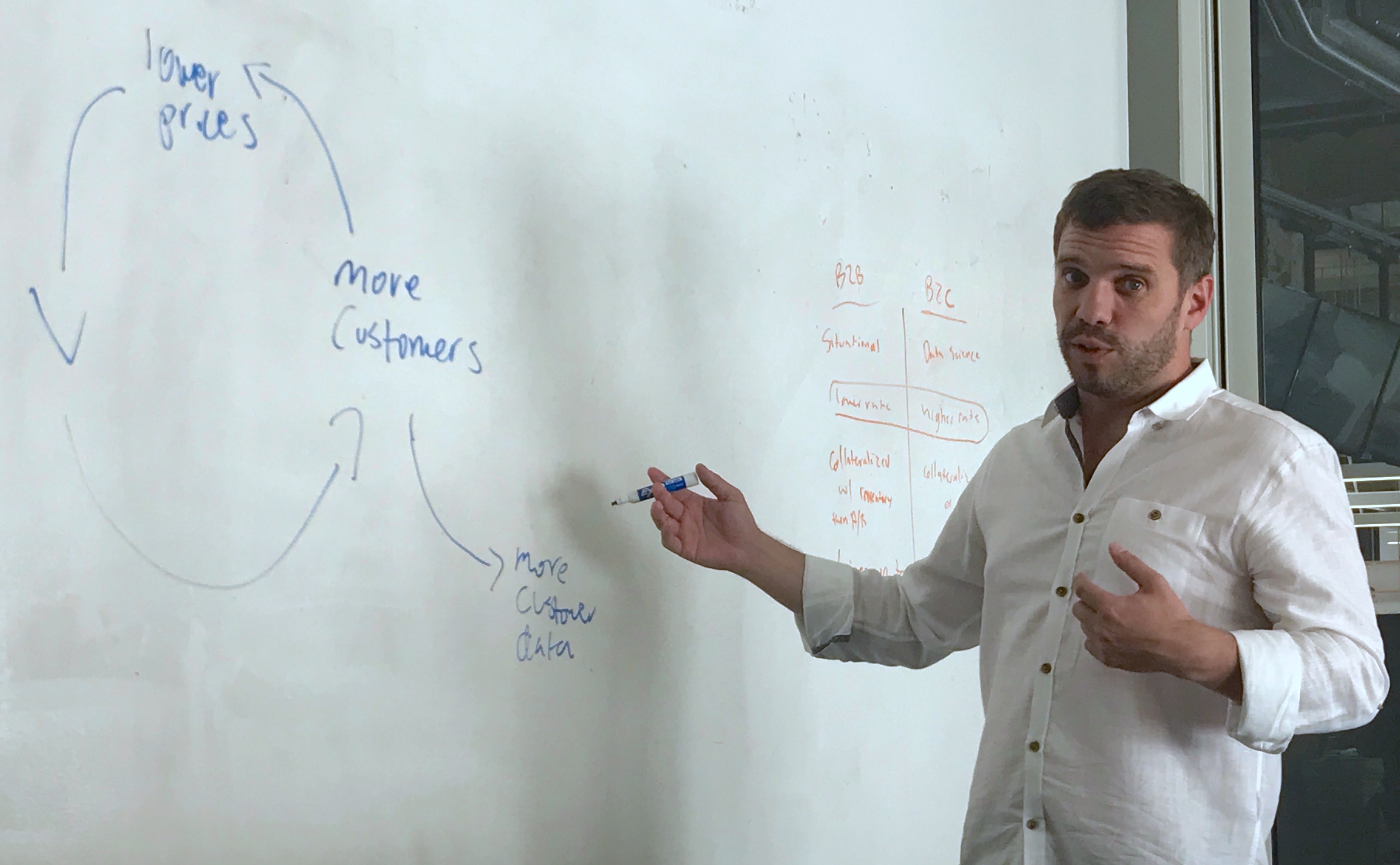

Ryan Petersen whiteboards his management frameworks

The first framework is from Petersen’s mentor and American business mogul Charlie Munger. It lays out the six stake-holders or ‘customers’ a business must satisfy to succeed. Here’s how Petersen describes them:

- Clients: The people who pay you money. For Flexport, we have both importers and exporters

- Vendors: The people you pay. For Flexport, who own the planes, ships, and trucks

- Employees: Make sure they’re treated well. It has to be a win-win trade.

- Investors: They deserve a return on their money. They took a risk

- Regulators: They decide who to give licenses to. For Flexport, there are 43 regulators in just the US who take an interest in imported products.

- Communities: Where you operate. Maybe one day that’s global society

“If you don’t have at least a B grade in everything and ideally an A, you’re probably not long-term sustainable” Petersen explains. It’s a smart lens for anyone assessing companies, whether that’s ones to work at, invest in, work with, or one you’re leading and trying to improve.

Take Airbnb for example. Clients generally love its alternative to hotels, they’ve been able to continuously recruit employees effectively, and investors have offered it billions and kicked in to help it survive COVID-19. But its vendor hosts and their neighbors have struggled with disruptive guests, and communities and their local regulators have clashed with the startup over its impact on housing supply. The six customers concept identifies where Airbnb needs to work harder.

The second framework Petersen developed himself for how to ensure a company’s core values persist as it scales. It lays out the six culture questions:

- Why?: Why do you exist? What’s your purpose, mission, vision, and impact?

- Who?: Who do you hire and what values and behaviors do you look for?

- What?: What are you focused on and what metrics do you use to measure success?

- How?: How do decisions get made and how do you shorten the feedback loop for improvement?

- When?: When should things get done and when should you ship your product?

- Where?: Where does your team feel like it belongs and how do you become more inclusive?

Petersen likens these tenets to addressing a medical condition. It’s easier if leaders build them into their culture early than trying to fix them later. “If you were to get these things right in any company, you’ll outperform” he believes.

To execute on these, Petersen built a team close to him that just “makes sure our OKRs (objectives and key results) are clear, that we’re running inclusive meetings with good documentation, that we’re holding people accountable.” The method is heavily influenced by Amazon’s corporate style. As Petersen told me last year, “The English language lacks a positive word for bureaucracy.”

Ryan Petersen

Taking process seriously has made the CEO a hit with his employees. “Working for Ryan accelerated my career at least a decade. He has the uncanny ability to push people to their peak performance” said Flexport’s long-time former VP of product Sean Linehan, who went on to found Placement. “Ryan is building the playbook for operationally-intense tech businesses. Building a global logistics behemoth from scratch is an insanely complex job. But Ryan thrives in complexity. Where most entrepreneurs fall apart, he hits his stride.”

With the economics headwinds we’re facing, Petersen will need that drive if he wants to bring Flexport public. As you might expect, he’s learning about it. “I like reading annual reports. It’s like a hobby of mine, particularly with my competitors” Petersen says. “I want to go public. But I don’t want to go public until we’re profitable because I don’t want to be at Wall Street’s whims. If you’re losing money and you’republic and Wall Street doesn’t like your stock, you can get into this death cycle.”

Being the CEO of a company that outperforms has opened doors to new mentors too, like executive coach Matt Messari, and Microsoft’s Satya Nadella. Petersen asked Nadella “How can you make learning and development measurable?”. Redmond’s head honcho answered “You don’t have to measure everything.” Petersen took the note. Sometimes, you just do what you think is right.

The Wartime CEO

Leading with his heart has steered Flexport to join the coronavirus relief effort in huge ways. “We were not put on this earth to lay in bed staying warm under the blankets. It’s time to step up and do something for the world” Petersen tweeted.

Flexport’s response started in Januarury with multiple blog posts per week laying out how COVID-19 was impacting global trade, how aid organizers could navigate supply chain issues, and how governments and private companies could help. Then it launched the Frontline Responders Fund and began routing all Flexport.org contributions to the cause, massively discounting freight forwarding costs to help get PPE wherever it’s needed.

Flexport.org launched the Frontline Responders Fund

“100% of your donation to this cause will go directly toward shipping masks to people on the front lines as fast as possible. I give you my word that we won’t waste a penny of your money” Petersen tweeted. Despite his business encountering its own troubles with global trade and demand disrupted, he shifted to spending his full time running Flexport.org and promoting the FRF. With the help of celebs like Arnold Schwarzenegger and Edward Norton, it’s raised over $7 million. The FRF has delivered over 6.9 million masks, 240,000 gowns, 1,000 ventilators, 155,000 gloves, and 250,000 meals for vulnerable populations.

Petersen hasn’t been shy about rallying more leaders to the cause, writing this expansive guide to the major bottlenecks blocking relief. “Philanthropists should also step up, lending money to organizations that have received purchase orders for PPE, but that can’t afford to buy the equipment unless they are paid upfront. Because they’ll get their money back when the pandemic subsides, this is one of the highest impact forms of philanthropy out there right now.”

That willingness to get involved has inspired his employees to roll up their sleeves too. “During a crisis, leaders really show the values they embody” says Susy Schöneberg, head of Flexport.org. After the COVID-19 outbreak, Ryan immediately offered us more resources to support our commercial and nonprofit clients. Over the last weeks, my days started and ended by talking to him – no matter what time is was.”

Ryan Petersen

From his vantage point, Petersen also has special visibility into who is trying to exploit the crisis. “Effective immediately Flexport will not ship personal protective equipment unless the customer can demonstrate which hospital system or other frontline emergency responder they are being provided to” Petersen wrote. “There are global shortages of these products, and it is immoral to allow war-profiteering from entrepreneurs looking to make an easy dollar.”

In the absence of proper federal crisis management, Petersen has become a defacto general in the war against coronavirus. “Given the scale of the problem and the complexity of the market failures outlined above, there’s no way for the US government to solve this on its own. But it can and must provide leadership, breaking down obstacles and coordinating the response of the private sector.” Until then, Petersen’s learning as fast as he can to become the wartime CEO needed right now.

Paraphrasing Kobe Bryant, Petersen concludes, “When you know what your goal is, the entire world is your library.”

For more of this author Josh Constine’s thoughts on tech, subscribe to his newsletter Moving Product

from TechCrunch https://ift.tt/3eTTpmw

0 comments:

Post a Comment