Preston Estep was alone in a borrowed laboratory, somewhere in Boston. No big company, no board meetings, no billion-dollar payout from Operation Warp Speed, the US government’s covid-19 vaccine funding program. No animal data. No ethics approval.

What he did have: ingredients for a vaccine. And one willing volunteer.

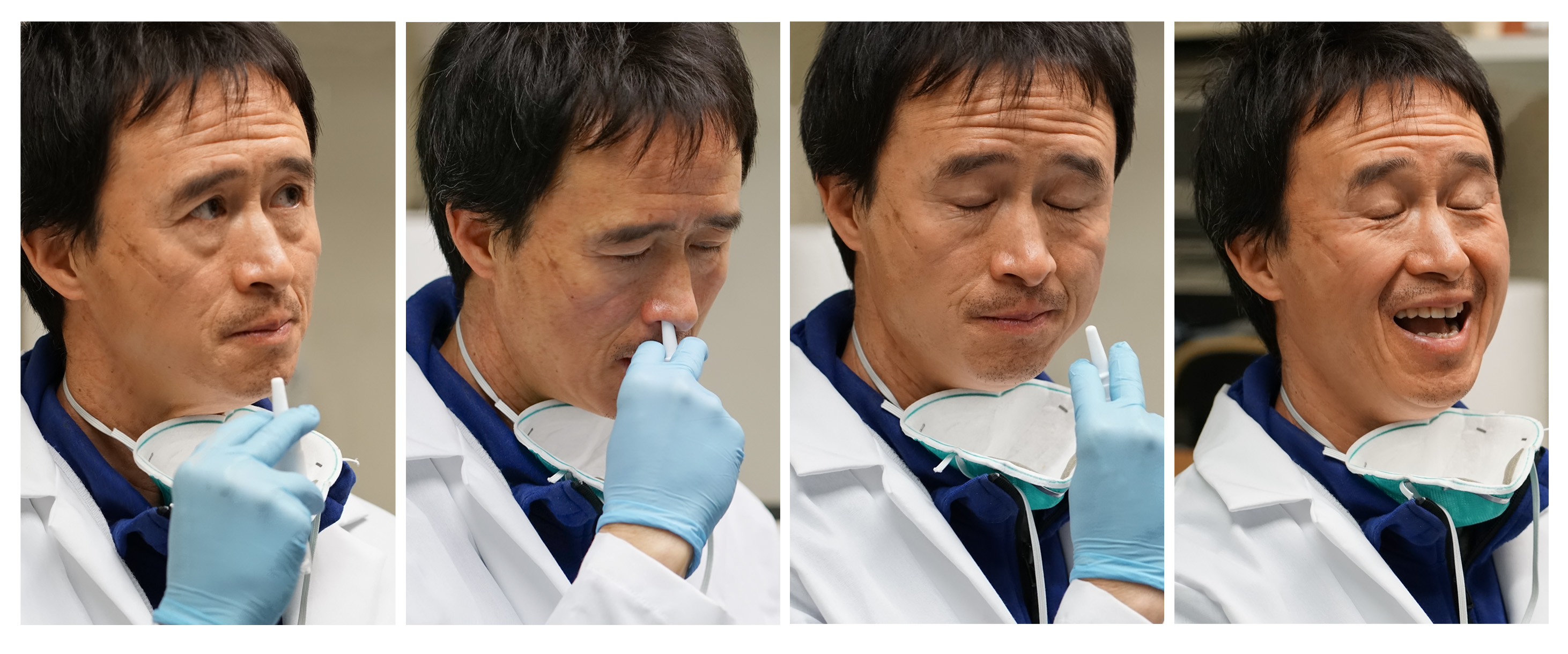

Estep swirled together the mixture and spritzed it up his nose.

Nearly 200 covid-19 vaccines are in development and some three dozen are at various stages of human testing. But in what appears to be the first “citizen science” vaccine initiative, Estep and at least 20 other researchers, technologists, or science enthusiasts, many connected to Harvard University and MIT, have volunteered as lab rats for a do-it-yourself inoculation against the coronavirus. They say it’s their only chance to become immune without waiting a year or more for a vaccine to be formally approved.

Among those who’ve taken the DIY vaccine is George Church, the celebrity geneticist at Harvard University, who took two doses a week apart earlier this month. The doses were dropped in his mailbox and he mixed the ingredients himself.

Church believes the vaccine designed by Estep, his former graduate student at Harvard and one of his proteges, is extremely safe. “I think we are at much bigger risk from covid considering how many ways you can get it, and how highly variable the consequences are,” says Church, who says he has not stepped outside of his house in five months. The US Centers for Disease Control recently reported that as many as one-third of patients who test positive for covid-19 but are never hospitalized battle symptoms for weeks or even months after contracting the virus. “I think that people are highly underestimating this disease,” Church says.

Harmless as the experimental vaccine may be, though, whether it will protect anyone who takes it is another question. And the independent researchers who are making and sharing it might be stepping onto thin legal ice, if they aren’t there already.

A simple formula

The group, calling itself the Rapid Deployment Vaccine Collaborative, or Radvac, formed in March. That’s when Estep sent an email to a circle of acquaintances, noting that US government experts were predicting a vaccine in 12 to 18 months and wondering if a do-it-yourself project could move faster. He believed there was “already sufficient information” published about the virus to guide an independent project.

Estep says he quickly gathered volunteers, many of whom had worked previously with the Personal Genome Project (PGP), an open-science initiative founded in 2005 at Church’s lab to sequence people’s DNA and post the results online. “We established a core group, most of them [from] my go-to posse for citizen science, though we have never done anything quite like this,” says Estep, also the founder of Veritas Genetics, a DNA sequencing company.

To come up with a vaccine design, the group dug through reports of vaccines against SARS and MERS, two other diseases caused by coronaviruses. Because the group was working in borrowed labs with mail-order ingredients, they wouldn’t make anything too complicated. The goal, says Estep, was to find “a simple formula that you could make with readily available materials. That narrowed things down to a small number of possibilities.” He says the only equipment he needed was a pipette (a tool to move small amounts of liquid) and a magnetic stirring device.

In early July, Radvac posted a white paper detailing its vaccine for anyone to copy. There are four authors named on the document, as well as a dozen initials of participants who remain anonymous, some in order to avoid media attention and others because they are foreigners in the US on visas.

The Radvac vaccine is what’s called a “subunit” vaccine because it consists of fragments of the pathogen—in this case peptides, which are essentially short bits of protein that match part of the coronavirus but can’t cause disease on their own. Subunit vaccines already exist for other diseases such as hepatitis B and human papillomavirus, and some companies are also developing subunits for covid-19, including Novavax, a biotechnology company which this month secured a $1.6 billion contract from Operation Warp Speed.

To administer its vaccine, the Radvac group settled on mixing the peptides with chitosan, a substance from shrimp shells, which coats the peptides in a nanoparticle able to pass the mucous membrane. Alex Hoekstra, a data analyst with an undergraduate degree in biology who previously volunteered with the PGP, and who also squirted the vaccine up his nose, describes the sensation as, “like getting saline up your nose. It’s not the world’s most comfortable feeling.”

Does it work?

A nasal vaccine is easier to administer than one which must be injected and, in Church’s opinion, is an overlooked option in the covid-19 vaccine race. He says only five out of about 199 covid vaccines listed as in development use nasal delivery, even though some researchers think it’s the best approach.

A vaccine delivered into the nose could create what’s called mucosal immunity, or immune cells present in the tissues of the airway. Such local immunity may be an important defense against SARS-CoV-2. But unlike antibodies that appear in the blood, where they are easily detected, signs of mucosal immunity might require a biopsy to identify.

George Siber, the former head of vaccines at Wyeth, says he told Estep that short, simple peptides often don’t lead to much of an immune response. Moreover, Siber says, he doesn’t know of any subunit vaccine delivered nasally, and he questions whether it would be potent enough to have any effect.

When Estep reached out to him earlier this year, Siber also wanted to know if the team had considered a dangerous side-effect, called enhancement, in which a vaccine can actually worsen the disease. “It’s not the best idea—especially in this case, you could make things worse,” Siber says of the effort. “You really need to know what you are doing here.”

He isn’t the only skeptic. Arthur Caplan, a bioethicist at New York University Langone Medical Center, who saw the white paper, pans Radvac as “off-the-charts looney.” In an email, Caplan says he sees “no leeway” for self-experimentation given the importance of quality control with vaccines. Instead, he thinks there is a high “potential for harm” and “ill-founded enthusiasm.”

Church disagrees, saying the vaccine’s simple formulation means it’s probably safe. “I think the bigger risk is that it is ineffective,” he says.

So far, the group can’t say if their vaccine works or not. They haven’t published results showing that the vaccine leads to antibodies against the virus, which is a basic requirement for being taken seriously in the vaccine race. Church says some of those studies are now underway in his Harvard laboratory, and Estep is hoping mainstream immunologists will assist the group. “It’s a little bit complicated, and we are not ready to report it,” Estep says of the immune responses seen so far.

A question of risk

Despite the lack of evidence, the Radvac group has offered the vaccine to a widening circle of friends and colleagues, inviting them to mix the ingredients and self-administer the nasal vaccine. Estep has now lost count of exactly how many people have taken the vaccine. “We have delivered material to 70 people,” he says. “They have to mix it themselves, but we haven’t had a full reporting on how many have taken it.”

One of the Radvac white paper’s co-authors is Ranjan Ahuja, who volunteers as an events manager for a nonprofit foundation that Estep started to study depression. Ahuja has a chronic condition that puts him at heightened risk from covid-19. Although he can’t say whether the two doses he took have given him immunity, he feels it’s his best chance of protection until a vaccine is approved.

Estep believes taking the peptide vaccine, even if it’s unproven, is a legitimate way to reduce risk. “We are offering one more tool to reduce the chance of infection,” he says. “We don’t suggest people change their behavior if they are wearing masks, but it does provide potentially multiple layers of protection.”

“If you are just making it and taking it yourself, the FDA can’t stop you.”

By distributing directions and even supplies for a vaccine, though, the Radvac group is operating in a legal gray area. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires authorization to test novel drugs in the form of an investigational new drug approval. But the Radvac group did not ask the agency’s permission, nor did it get any ethics board to sign off on the plan.

Estep believes Radvac is not subject to oversight because the group’s members mix up and administer the vaccine themselves, and no money changes hands. “If you are just making it and taking it yourself, the FDA can’t stop you,” says Estep. The FDA did not immediately respond to questions about the legality of the vaccine.

Estep says the group did seek legal advice and its white paper begins with extensive disclaimers, including a statement that anyone who uses the group’s materials takes “full responsibility” and must be at least 18 years old. Among those who Estep says advised the group is Michelle Meyer, a lawyer and ethics researcher at Geisinger Health System, in New York. In an email, Meyer declined to comment.

Given the international attention on covid-19 vaccines, and the high political stakes surrounding the crisis, the Radvac group could nevertheless find itself under scrutiny by regulators. “What the FDA really wants to crack down on is anything big, which makes claims, or makes money. And this is none of those,” says Church. “As soon as we do any of those things, they would justifiably crack down. Also, things that get attention. But we haven’t had any so far.”

Self-experimentation

According to Siber, experimenting on oneself with covid-19 vaccines wouldn’t have any chance of winning ethics approval at any university in the US. But he acknowledges there is a tradition among vaccinologists of injecting themselves as a quick and cheap way to get data. Siber has done so himself on more than one occasion, though not recently.

The chance to speed up research makes self-experimentation tempting even today. There have been reports of Chinese scientists taking their own covid-19 vaccines. Hans-Georg Rammensee, of the University of Tubingen, in Germany, says he injected a covid-19 peptide vaccine into his abdomen earlier this year. It caused a bump the size of a ping-pong ball and a profusion of immune cells through his blood.

Rammensee, who cofounded the company CureVac, says he did it to avoid red tape and quickly get some preliminary results about a vaccine being developed at his university. He says it was acceptable to do so because he is a “renowned expert in immunology” and understood the risks and implications of his action. “If someone like me who knows what he is doing [does it], it’s fine, but it would be a crime for a professor to tell a postdoc to take it,” Rammensee said in a phone interview. He claims Germany has no clear rules on the subject, leaving self-experiments in a gray zone of actions which, as he puts it, “are not forbidden and which are not allowed.”

Because more people are involved in the Radvac project, it may be viewed differently by authorities, who could decide the group is in fact operating an unsanctioned clinical trial. In recent weeks, Estep and other Radvac members have started to publicize their work and contact acquaintances to encourage them to participate.

“He called me and said ‘Do you want it?’ and I said ‘no.’”

“It’s real, he’s a solid scientist, but I wouldn’t do what he is doing,” said one executive to whom Estep offered the vaccine. The executive asked to remain anonymous because he doesn’t want to be associated with the effort. According to the executive, “He called me and said ‘Do you want it?’ and I said ‘no.’ ‘Do you want me to send you some?’ I said ‘No, I am not going to do anything with it, so don’t waste it on me.’ I told him, ‘The less I know, the better.’”

Whether or not regulators step in, and even if the vaccine proves to be a dud, the DIY covid-19 vaccine is already changing the attitudes of those who’ve taken it. Hoekstra says that since twice spraying the formulation into his nose, he moves through an “unsafe” world differently.

“I am not licking doorknobs,” says Hoekstra, who joined the group after departing his day job due to the shutdown. “But it’s an amazingly surreal experience knowing that I may have an immunity to this constant danger [and] that my continued existence through this pandemic will be a useful dataset. It lends a level of meaning and purpose.”

I asked Hoekstra if I could join the group and get the vaccine, too. “Consider the invitation open,” he said.

from MIT Technology Review https://ift.tt/2EqQKTr

0 comments:

Post a Comment