Meili Gupta is about to ask another question.

A poised and eloquent rising senior at elite boarding school Phillips Exeter Academy, Gupta, 17, is anything but the introverted, soft-spoken techie stereotype. She does, however, know as much about computer science as any high school student you’d ever meet. She even grew up faithfully reading the MIT Technology Review, the university’s flagship publication, which shows, because Meili is the most ubiquitous student attendee at EmTech Next, a conference the publication held on campus this past summer on AI, Machine Learning, and “the future of work.”

Ostensibly, the conference is an opportunity for executives and tech professionals to rub elbows while determining how next-generation technologies will shape our jobs and economy in the coming decades.

For me, the gathering feels more like an opportunity to have an existential crisis; I could even say a religious crisis, though I’m not just a confirmed atheist but a professional one as well. EmTech Next, as I experience it, is a referendum on what it means to be human at a time when tech is redefining how we relate to one another and to ourselves.

In short: will tomorrow’s leaders, despite good and ethical intentions, ultimately use their high-tech tools to exploit others ever more efficiently, or to find a better path forward?

But I’ll get to all of that in a little while, including why it’s so unusual for someone like me to even attend such a conference, much less with a press pass.

First, back to Gupta, who has come to the conference prepared. Not that she completed any conference-specific homework assignments in advance, it’s just that each time she steps up to the microphone to kick off a Q&A session with another thoughtfully composed and energetically delivered mini-inquiry into the fate of our most dynamic industries, she not only asks about the future of work, she embodies it.

“I grew up with a phone in my hand,” Gupta told me in an interview conducted during the conference, and “most people [in my classes] have covers for the cameras on their computers.”

As managing editor for Exeter’s STEM magazine Matter, she published thoughtful analyses of the ethical challenges inherent in issues like AI and climate change. It’s a topic she’s been interested in since she walked on campus — Gupta took the senior-level course “Introduction to Artificial Intelligence” as a high-school freshman. She also took classes on and learned about self-driving cars and computer vision as well as setup an independent study on machine-learning algorithms. This fall, she began her senior year with a course called “Social Innovation Through Software Engineering,” in which students pick a local project and develop software towards doing social good. (Raise your hand if this resembles what you did with your teenage years).

And Meili does want to do “social good.” She considers tech ethics her generation’s job. She’s already well aware computer programmers need to learn to make less-biased algorithms, and knows this will require tech companies and the public to demand fairness and ethics. She wants to help address inequality, and is acutely aware of the irony that her superb education is the very embodiment of inequality.

After all, our social infrastructure allows, even cheerleads for certain people to learn so much more than others. It’s hardly news those same people are poised to dominate the future. What is noteworthy, however, is the rise of a class of people who are not only positioned to shape the future of the economy according to their will, but who simultaneously believe their own efforts will be necessary and sufficient to correct the injustices of that unequal future.

Students and alumni of elite institutions like Exeter, or MIT and Harvard (where I serve as a chaplain) are typically trained to see ourselves as generous, caring, and concerned citizens. We are not ignorant or callous to the suffering of others who are less fortunate, we tell ourselves. To the contrary, we are all about “service.” We will surely help others if — when — we succeed. Actually, it’s important we succeed as much as possible; only then will we have the resources necessary to help.

And yet, another narrative goes, we are also the best. We are special, exceptional, gifted. We aspire to inclusiveness. But we’re also still taught: be aggressive. Go out and win. Seize every opportunity.

What if we can only have one side of the coin?

The Student Winners Who Take All

Anand Giridharadas (Photo by Matt Winkelmeyer/Getty Images for WIRED25)

In his book Winners Take All, writer Anand Giridharadas critiques what he calls the religion of “win-winism”: the belief that the people whose ever-increasing domination of our social, economic, and political world are not only capable of fixing the problems of inequality and injustice their domination causes, but are in fact ideally positioned — by virtue of their victories — to be saviors and liberators to those who’ve lost.

Thus, you have Mark Zuckerberg championing freedom of expression as a core democratic belief while simultaneously undermining democracy by taking millions to publish false political ads. Or you have Marc Benioff proclaiming the end of capitalism and a new era of ethics while maintaining his own billionaire status and defending Salesforce’s support of ICE, even as undocumented children are separated from their families.

As we talk in an MIT Media Lab conference room, Gupta’s Chinese-born mother, who came to the U.S. just out of graduate school after student-led protests famously rocked Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, looks on, beaming with pride at her daughter’s obvious excellence.

Yet, what will the post-college experience be like for someone who developed technical and interpersonal skills like Gupta’s as a teen? After fifteen years at Harvard and MIT, I can tell you: people will throw jobs and money at her. I mean, you never know who will end up a billionaire, but she’s unlikely to end up sleeping in her car.

Or, let’s not make this about Gupta, whom I genuinely like and wish well. The bigger question is: Will the future of work be a dystopia in which thoughtful young people like Gupta tell themselves they want to save the world, but end up ruling the world instead? Or can the students now attending elite private schools and universities and conferences at MIT use their deftness with the master’s tools to dismantle their own house?

A Nonreligious Chaplain

Stepping back though, it might help to explain how a nonreligious chaplain even got involved in tech and the future of work in the first place.

I was a college religion major who thought about becoming a Buddhist or Taoist priest but ultimately got ordained as a rabbi and became clergy for the nonreligious (I’ve been the Humanist Chaplain at Harvard University since 2005).

A decade ago, I wrote a book called Good Without God, about how millions of people live good, ethical, and meaningful lives without religion. Even so, I argued nonreligious people should learn from the ways religious communities build congregations to generate mutual support and inspiration. I squabbled publicly with fellow atheists like Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and Lawrence Krauss over their aggressive condemnation of every aspect of religion, even the parts that inspire working people who haven’t had the extraordinary fortune to become as educated as them. And, attempting to focus on the positive rather than simply telling others what not to do, I then co-founded and led (until it closed last year) one of the world’s largest “godless congregations.”

“Good Without God” by the author.

Sounds completely unrelated to anything you came to this site to read about? If so you’re right, and that’s the point. Until recently, I’d never been involved in tech as anything beyond an enthusiastic — and at times addicted — consumer.

The Ethics Of Technology

Things began to evolve in early 2018, when I joined MIT’s Office of Religious Life (which soon changed its name to the Office of Religious, Spiritual, and Ethical Life or ORSEL) as its Humanist Chaplain. The office also placed me into a new role called “Convener” for “Ethical Life,” asking me in other words to convene people across campus to reflect on how to live an ethical life from a secular perspective. Turns out, nonreligious ethics are important on a top tech campus like MIT, an institution so secular that only around 49 percent of its students consider themselves religious.

In the past, I might have declined MIT’s offer (my responsibilities at Harvard and elsewhere kept me busy enough, thank you very much). But, if I’m being honest, when I was asked to join, I was undergoing my own crisis of conscience. I’d begun to seriously question my own ethical vision.

No, I hadn’t found God (very funny). I had, however, discovered some serious flaws in the values I’d grown up with as a relatively privileged, straight, cis-gendered white man who believed in the power and virtue of American capitalism. That’s relatively privileged, by the way: my mom was a child refugee who came to the U.S. from Cuba with nothing. Both my parents attended community college, my dad never graduated, and the only money I got from him after he died when I was a teenager came from his Social Security checks.

Still, I realize now that I managed to grow up, do seven years of grad school, and start a decently prominent career around “ethics” without fully recognizing just how much of American culture and Western civilization is fundamentally unjust.

Reading Ta-Nehisi Coates’ book Between The World and Me in 2015, I started thinking about how slavery was not only the moral evil I’d always considered it — it was the single. largest. industry. in the founding decades of American history. As the New York Times Magazine’s “1619 Project” demonstrated, the political and economic exceptionalism of this country, which I embraced as the son of a refugee from a brutal Communist regime, was itself built entirely on a foundation of brutal oppression and exploitation.

“Between the World and Me” by Ta-Nehisi Coates

With Donald Trump’s election, I could no longer avoid the conclusion that white supremacy and kleptocracy are alive and well, here and now. Then came #YesAllWomen and #MeToo. Though I’d been raised as a proud feminist, I found myself reflecting on some of the harmful ways in which I’d been taught to be a man. Never admit vulnerability, except maybe privately and ashamed, to a woman on whom I was over-relying for emotional support. Be aggressive. Always win, because losers are the most valueless and wretched things on earth.

Like millions of others, I’d spent my life under the sway of a certain strain of American meritocracy which preaches a relatively secular but nonetheless fantastical dogma: that people like me are gifted, talented winners who should devote most of our energy in life to achieving as much personal success as humanly possible. And if all our winning and dominance ever starts to seem unfair, even a bit cruel or oppressive? No worries. We’ll justify it all by “giving back,” through community service or philanthropy or both.

That’s the level of cynicism and self-doubt I was experiencing when I got to MIT last year. Then one of my students noted, “if all companies started by MIT alums combined into a country, it’d be in the G20.” Most of my life, I’d have taken her comment as a point of pride. Instead, I began to realize: maybe places like this are the problem, simply by amassing so much of the world’s wealth and power that billions of people are left without virtually any.

Maybe people like me, proudly and too uncritically devoting ourselves to serving these places, are the problem.

In short, maybe I’m the problem.

Enter Giridharadas, the critic of contemporary capitalism, whose work was introduced to me last year by a Harvard Business School student. When Winners Take All came out last fall, it had students gasping as they read it in the halls of HBS before holiday break. A fast-talking, 38-year-old Indian American with an all-black wardrobe and a preternatural ability to go viral on Twitter, Giridharadas argues “we live in an age of staggering inequality that is fundamentally about a monopolizing of the future itself,” as he told me for my first TechCrunch column in March.

“The winners of our age, the people who manage to be on the right side of an era of precipitous change and churn, have managed to build, operate, and maintain systems that siphon off most of the fruits of progress to them,” he continued. A true iconoclast, Giridharadas is utterly unapologetic in criticizing the biggest heroes of the past generation: business titans and philanthropists like Zuckerberg and Bill Gates who give away billions but, he argues, do so mainly to hide greed, exploitation, and the subversion of democracy.

Through his words, I saw myself and the status quo I had helped maintain by failing to criticize the structures in which I existed, and I felt ashamed. But unlike with the shame I felt as a young man internalizing toxic masculinity, I didn’t want to hide my feelings, repress them, or confess them only to my wife. I wanted to own them publicly and do something about them.

During this same time, I got acclimated at MIT and found myself almost obsessively drawn to reading about “the ethics of technology,” an emerging but amorphous field of study in which scholars, activists, policy makers, business leaders and others debate the societal ramifications of technological change.

Tech, after all, has become the ultimate secular religion. What else so shapes today’s values (innovation is always good!); requires daily rituals (in ancient times, we prayed when we awoke, when we went to sleep, and throughout each day; that is now called, “checking our phones”); offers abundant prophets (VC’s, TED talkers, and what The New York Times writer Mike Isaac aptly calls “The Cult of the Founder”); and maybe even deities (as in the semi-disgraced tech hero Anthony Levandowski’s seemingly sincere attempt to found a church worshipping the AI God of the future)?

Whether we think of tech like a religion or an “industry” (though what industry isn’t technology-based today?), it’s clearly causing terrible suffering and division. Uber and Lyft mobilize millions of drivers worldwide, and perhaps the majority make poverty wages. Platforms like YouTube and Facebook “democratize” culture, empowering billions to post their opinions. To do so they design algorithms so intentionally addictive and inflammatory, the world seems to have lost much of the ability it was in the process of gaining to conduct free, fair elections that enfranchise minorities and working people. And giant data centers powering all this “world changing” AI are worse for the climate than hundreds of trans-Atlantic flights. I could go on.

So I began a column at TechCrunch and took a year-long sabbatical to study the ethics of technology, of which “the future of work” is part. Which brings us to this summer.

Feeling like an eager and anxious MIT student myself, I head to EmTech Next with my press pass and my first-ever assignment as a reporter. I’m anticipating juicy work, investigating the ethical stances of companies and speakers slated to be on hand at the conference.

Walking over, however, I realize I’m stuck on a more basic question. What exactly does the phrase “the future of work” even mean?

What even is “The Future of Work?”

The past decade has brought an explosion in books, articles, commissions, conventions, courses, and experts claiming to help determine “The Future of Work.” Influential ‘FoW’ authors have run think-tanks and universities, advocated for the disabled and disadvantaged, advised harried parents, and even run for major political office. Earlier this year, California Governor Gavin Newsom even announced a prestigious “Future of Work Commission,” the first of its kind to serve in such a statewide capacity.

In tech ethics circles, the phrase references a crucial subgenre in which some of the fiercest policy debates of our time rage: are the jobs tech companies create actually good for society? What will we do if/when robots take them? And how does changing our work also change how we think about our lives and our very humanity?

The phrase dates back over a century, perhaps coined by the ironically named British-Italian economic theorist L.G. Chiozza Money, who argued in “The Future of Work and Other Essays” that science had already solved “the problem of poverty” — if only humanity could get beyond the disorganization and waste characterizing competitive capitalism at the time (!).

More recently, a TIME cover story on “The Future of Work” from a decade ago helped popularize what we tend to mean by the phrase today. “Ten years ago,” it began, “Facebook didn’t exist. Ten years before that, we didn’t have the Web.” The sub-header asked, “Who knows what jobs will be born a decade from now?”

Time’s “The Future of Work” cover (May 25, 2009).

Convenient, because of course we now know exactly what jobs have been born.

TIME’s story featured ten predictions: tech would top finance as the leading employer of elites; flexible schedules and women’s leadership rising; traditional offices and benefits declining. It’s not that the claims turned out to be egregious; but when you’re forecasting general trends, value lies in questions of nuance, like, “to what extent?” Sure, women made gains over the decade, but who would say they did to an acceptable degree?

Some more nuanced FoW books, like The Second Machine Age, by MIT Professors Erik Brynjolffson and Andrew McAfee, take the optimistic perspective on tech — that “brilliant machines” will soon help create a world of abundant progress, exemplified by the success of Instagram and the billionaires that company and its business model created. But Brynjolffson and McAfee compare Instagram to Kodak, without offering solutions to the problem that Kodak once employed 145,000 people in middle-class jobs, compared to a few thousand workers at Instagram.

“The Second Machine Age” by Erik Brynjolffson and Andrew McAfee

I would come to wonder, is philosophizing about “the future of work” just a way the richest, most influential people in the world convince themselves they care deeply about their employees, when what they’re doing is more like strategizing how to continue to be exorbitantly powerful in the decades to come?

“Diverging trajectories,” other euphemisms, and billionaire humanism

Well, yes.

A sleek new report by the McKinsey Global Institute, “The Future of Work in America,” emphasizes “diverging trajectories,” “different starting points,” “widening gaps,” the ‘concentration’ of growth, and other euphemisms for rising inequality that will almost certainly typify the near future of work, fueling growing anger and polarization. Their point is fairly clear: increased polarization means certain sectors like health and STEM are poised for big gains. Other fields like office support, manufacturing production, and food service jobs could be hit hard.

The “Shift Commission,” an initiative funded by now likely Presidential candidate Michael Bloomberg, produced another influential Future of Work report in 2017. In the Shift report, Bloomberg’s organization, in partnership with centrist think tank New America, emphasizes more future work for older people, concern about jobs in places that have been “left behind,” and general concern that the country’s economic dynamism might slow.

Michael Bloomberg (Photo by Yana Paskova/Getty Images)

The report describes four scenarios under which work in America might change in 10-20 years. Will there be more or less work, and will that work be mostly “jobs” in the traditional sense or “tasks” in the sense of projects, gigs, freelancing, on-demand work, etc.? Each scenario is named after a game: Rock Paper Scissors, King of the Castle, Jump Rope, and Go. Which reminds me of a certain Twitter meme:

Absolutely no one:

No one at all:

Literally no person:

The Shift Commission: “Hey, let’s make our deliberations over whether people will be able to find decent jobs a generation from now, or whether almost everyone but us will wind up in poverty, into a cutesy game!”

Sure, part of the “winning” strategy for doing business successfully has always been to have a little fun — and do a little good — while setting the rules of the competition heavily in one’s own favor. But will the different possible outcomes of the future of work be perceived as ‘fun and games’ by the losers of those games as much as by the victors?

The Shift report, Bloomberg wrote, aimed to “strip away the hyperbole and the doomsday tone that so often characterize the discussion of [the future of work,]” but the report’s tone and content have problems of their own.

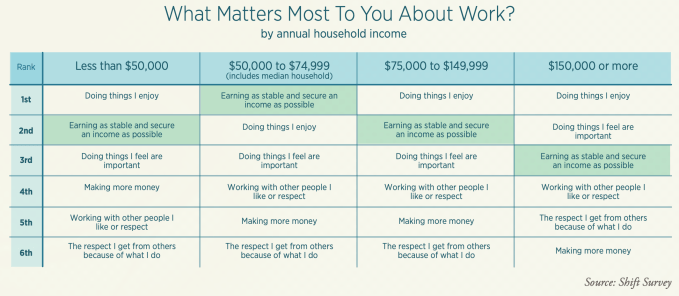

Organizers highlight a survey finding “only people who make $150,000 a year or more say they value doing work that is important to them. Everyone else prioritizes an income that is stable and secure.” The basis for this conclusion? Given several choices to rank in terms of “What Matters Most to You About Work?” only the highest income bracket chose “doing things I feel are important” over “earning as stable and secure an income as possible.”

But if people are so scared of falling into destitution that they’ll prioritize security over meaning, that doesn’t mean we’ve suddenly discovered some Grand Truth about how only rich people would like to lead meaningful lives.

Via Shift Commission Report on Future of Work

Also, all the Shift/Bloomberg scenarios strike me as dystopian to some degree: all seemingly prophesize increasing screen addiction and competition for labor among everyone but an ultra-wealthy, ultra-educated elite continuing to gain power no matter which “game” becomes reality. None of the options is a more regulated, less unequal, dramatically more equitable future.

Which makes me think that all the various scenarios explored in the Shift, McKinsey, and other reports are just … scenarios, like when talk show hosts with thick Brooklyn or Bahstan accents break down who is definitely going to win next year’s Super Bowl or NBA Finals.

Now, I confess: instead of downloading the latest hip podcast from The New Yorker or Pineapple Street Media or wherever, in my free time, as I have since I was a kid, and like so many men, I listen to other men sitting around tawking spawts: guessing the betting lines, predicting the winners and losers, the MVP’s and the goats.

It’s a terrible hobby, but I’m basically addicted, though happily not to the sports gambling that underwrites a lot of my favorite sports talk shows. I don’t gamble myself, but I understand the appeal of betting on games and players and outcomes. And you don’t need to be a bookie in Vegas to understand why so many men like me spend our time this way: we want to know what will happen. We want to be prophets. We want to be in control. We want poetic justice. But we have no realistic way to get any of that, so we immerse ourselves in a kind of religious ritual of persuading ourselves we’re in control. A daily illusion, a form of alchemy, a pseudoscience.

Is VC the same thing? Is a lot of tech journalism? And even a fair bit of what passes for tech ethics?

I don’t know, but I do know that in addressing whether their various Future of Work scenarios will yield accurate predictions, Shift Commission organizers offer a typical FoW response. They quote John Kenneth Galbraith’s statement that, “We have two classes of forecasters: Those who don’t know — and those who don’t know they don’t know.”

Maybe what all of this underscores is that any hope most of us might have for a benign future of work is increasingly projected on to what I’ve come to think of as “billionaire humanism.”

Billionaire humanism is what happens when we say we value every human life as primal and equal, but in practice we are just fine if most humans suffer under the stress of every manner of precariousness, from birth to death, so a relative handful of humans can live lives of extraordinary freedom and luxury.

Billionaire humanism is a world in which, as Ghiridaradas pointed out to me for TechCrunch, we invent every manner of new shit, and yet life expectancy goes down, literacy goes down, and overall health and well-being decline. Billionaire humanism is when we experience that as our daily reality, yet we are expected to be grateful for “progress,” as if the current state of things is the best of all possible worlds and the future is sure to be as well. That’s why it’s appropriate to be angry when we contemplate these questions.

Which brings me back to Gupta. She was, when I spoke to her at MIT, feeling well aware that she was the future of work. For a high school student (or even if she were in her twenties), she shows such an impressive awareness of and interest in the ethical issues in AI and environmental policy-making.

But when I ask her what she wants to get out of attending EmTech Next, she replies, “I was hoping to learn some insight about what I may want to study in college. After that, what type of jobs do I want to pursue that are going to exist and be in demand and really interesting, that have an impact on other people?”

In other words, Gupta understandably also seems to want to know the future so she can control it. But is the idea to get a job that’s in-demand and interesting? Or one that makes an “impact?” Sure, one can dream of both, but what if one needs to choose more of one over the other? There’s a fundamental ambivalence to her response — a kind of agnosticism, a hedging of one’s bets, an “it depends.”

And if “it depends” is what studying and conferencing about the future of work ultimately boils down to, then it should not count as the kind of “important” undertaking the richest cohort in the Shift Commission study said it valued so much.

What Kind of Future, and For Whom?

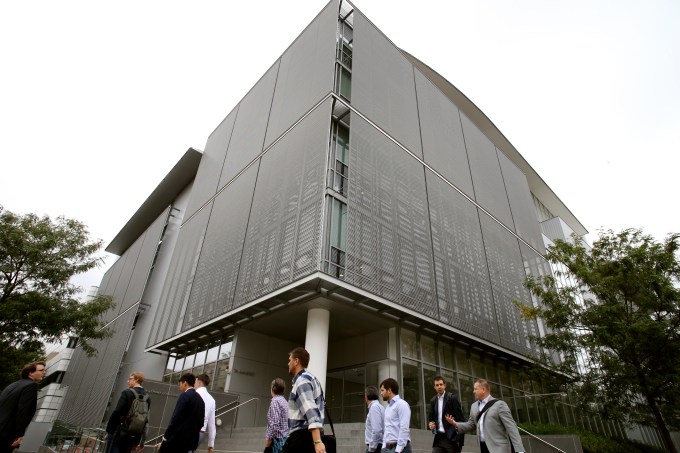

David Autor via MIT Technology Review

As the EmTech Next conference begins, I’m as ambivalent as ever. We’re in the auditorium on the top floor of the newer of two buildings for MIT’s Media Lab (the famous “future factory” as it is widely known). The Media Lab building is such an impressive display of modern design and experimental robots-in-progress peeking out from behind glass lab walls stretching up to cathedral ceilings that even a trendily-dressed preadolescent girl roaming the halls with her father, a messy-haired worker here, can be overheard saying, “I love your work. It’s so cool in here…”

The conference’s opening speaker, MIT economics professor David Autor, is presenting on his latest paper, “Work of the Past, Work of the Future.” Autor studies displaced workers: non-college educated, mostly men in manufacturing who’ve endured what he calls the “shocks” of automation. These workers could once earn premium wages in big cities, which mitigated against toxic inequality but no longer, Autor explains. With most such jobs automated out of existence or outsourced to other countries, big cities have become concentrated havens of opportunity for richer, younger, healthier, and highly educated people.

Autor’s talk focuses on “rebuilding career pathways” for the less educated, which would be enormously invigorating, he says, for our sense of shared prosperity.

That’s unobjectionable, but peering through my Giridharadas lens I wonder, will the future of work, as economists like Autor envision it, involve a never-ending, enormous divide between haves and have-nots? Are band-aid solutions to market-driven inequality the best we can hope for? (Okay, maybe Autor is proposing minor surgery — but on a gaping, cancerous wound).

In a vacuum, it sounds appealing to give poorer workers more “training,” more “refined skill sets.” But such ideas tend to suck up whatever bandwidth the busy people at meetings like EmTech Next are willing to devote to thinking about social problems. So we get to feel good about our magnanimity for a couple of hours, then continue winning to an obscene degree, rather than ever substantively addressing the savage exploitation, racism, and greed at the heart of why people are poor in the first place.

The opening panel gets particularly depressing when it turns to Autor’s co-panelist Paul Osterman, a professor of human resources management at MIT’s Sloan business school. Osterman’s book Who Will Care For Us and his remarks here are on improving conditions for the millions of “direct care workers” (like nurses and aides) who will attend to aging Americans in the coming years. We need more and better training options for such workers, Osterman says.

Sure enough! But is THAT the big idea for the future of work? Improve opportunities to clean up after rich people like the ones attending this conference, when we get too old or sick to clean our own bodies? As I write this, I think of my dad, who grew up poor, never finished college, and tried hard but never “graduated” to a higher social class. “He had champagne taste, and a water budget,” his sister once told me about him many years after he died.

In the final weeks of his life, during my senior year of high school, dad sometimes needed my help getting his emaciated, cancer-stricken body to the toilet. The stress and sadness of that experience stuck with me for life; I have tremendous respect for people performing caring work professionally every day. But it is infuriating to hear a room full of bosses nodding: not only should millions more poor people do such jobs, it’s also a great opportunity for them. They should be grateful we’re planning out their future so brilliantly and thoughtfully.

And that’s what economists like Autor and Osterman, alongside an entire genus of similar thinkers, seem to me to be saying: that “we,” the ingenious few who control money and policy, are here to decide the fate of “they,” the poorer people who aren’t fortunate enough to be in the room with us today. By all means, let’s ease people’s suffering and “give back” to them.

But do we have a responsibility to actually bring them into the room with us to make decisions as equals?

The economics of real, structural change

The “future of work” ethos may be perfectly standard fare for the kind of economically centrist perspective to which I used to subscribe and which has characterized most of the U.S. Democratic party’s leadership since Bill Clinton’s ascendance. But it doesn’t represent what Elizabeth Warren has taken to calling “Big, Structural Change,” or what Bernie Sanders, hands akimbo, white hair and spittle flying, calls, “Revuhlooshun!”

Yes, let’s talk about how to pay health aides and construction workers a little better and how to “give back,” but by no means should we upend our economy to pay reparations, or tell the global rich to “take less,” as Giridharadas demands in his writing.

I talked with Autor just after the conference, and I admit part of me wanted him to make things simple by being a bad guy: sympathetic to the rich, condescending to the poor, a neoliberal hack making techies feel good about themselves by proposing partial solutions that don’t challenge power or privilege. It’s hard to pin him that way, though, and not just because he’s been wearing a gecko earring since he bought it in Berkeley with his wife decades ago.

Yes, Autor told me, he is a capitalist believer in market economies. Yes, labor unions have bashed his work at times, in a “knee-jerk” way he finds “super irritating.” But he sees improved dialogue of late, now that he’s come to believe organized labor needs a larger role in society. And labor leaders have “accepted that the world’s changed,” Autor says, “not just because of mean bosses and politicians … there are underlying economic forces that impact the work people do.”

Autor is also a Jewish liberal who spent three years worth of his own work time teaching computer skills to poor, mostly Black people as an early employee of GLIDE, a large United Methodist church in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district now famous for its 100-member gospel choir, LGBT-affirming attitude, and a community clinic serving thousands of homeless people each year from the church’s extensive basement. That’s not nothing.

The GLIDE Ensemble performs during a Celebration of Life Service held for the late San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee on December 17, 2017 in San Francisco, California. (Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

“I met twice with President Obama,” Autor proudly volunteers. So I figure I’ll ask him about Senator Warren, a prominent Presidential aspirant who literally lives in our neighborhood, and who is building her message around economic justice. Autor has also met with her. He likes her approach to antitrust regulation and consumer protection. But her proposal to pay off student loans is “dumb,” he says, because it will transfer too much money to the rich.

But is that our biggest concern when trying to make inclusive economic policy? All the rich people who are apparently taking out student loans?

Of course, my questions about Autor and Osterman are really about practically the entire field of economics. For generations, economists have asked us to take on faith that their unique genius can calibrate our financial system to advance prosperity and avoid collective ruin. But what about using that same genius to make the system itself more just and equal?

That, they say, is beyond their (or anyone’s) powers.

“Economics really is a branch of moral theology,” said the great tech critic Neil Postman, in promoting his 1992 book Technopoly, about how technology had (already!) become a religion and that America was becoming the first nation to adopt it as its official State Spirituality. “It should be taught more in divinity schools than in universities.”

What about Universal Basic Income?

Supporters of Democratic presidential candidate, entrepreneur Andrew Yang march outside of the Wells Fargo Arena before the start of the Liberty and Justice Celebration on November 01, 2019 in Des Moines, Iowa. (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

Martin Ford’s book The Rise of the Robots looks at the future of work less optimistically, lamenting that new industries will “rarely, if ever, be highly labor-intensive,” and ultimately calling for a Universal Basic Income (UBI) — a favorite solution of many tech leaders and future-of-work analysts alike, including Andrew Yang, the tech entrepreneur and unlikely top-tier Democratic presidential candidate.

Yang’s rise in popularity owes much to his identification with the tech community, including support from icons like Elon Musk. And in referring to his own prescribed version of UBI as the “Freedom Dividend,” Yang nods not only to ‘freedom,’ long a staple of presidential rhetoric on left and right, but also to the ‘dividends’ paid by companies to shareholders. At a time when some politicians propose ending capitalism as we know it, Yang’s language suggests remaking America in Big Tech’s image.

It’s tempting, for obvious reasons, to envision monthly thousand-dollar checks for millions of struggling Americans. Yet for all its fanfare, UBI does essentially nothing to address the metastasizing cancer of structural inequality in American society. Under the “freedom dividend,” the poor remain poor, while the rich almost certainly continue an inexorable upward march toward ever greater wealth. All of this would be essentially by design.

Think about the staggering inequality tech entrepreneurs have already overseen in and around Silicon Valley: homelessness, gentrification, and wage stagnation for all but the rich. That funneling of money to the wealthiest is not a bug in tech’s code. Economic exploitation was a core feature of Silicon Valley back in the 70’s and 80’s. It remains a core feature today.

The Freedom Dividend, in practice, will involve most Americans scraping by on (maybe!) a thousand more dollars a month, while elites gain ever firmer control over the entire world around them. That’s not identifying and creating structural change in the future of work.

A maddening feedback loop: the problem with “mission-driven” work

Karen Hao via MIT Technology Review

After the Autor and Osterman panels, I head out to interview Karen Hao, the AI reporter for the MIT Technology Review. Less than a decade out of her undergraduate degree at MIT, Hao writes mainly on the ethical implications of AI technologies and their impact on society, both in thoughtful articles and a snappy email newsletter, the Algorithm. Her sources and inspiration for stories are often her former dormmates and classmates.

She gravitated towards ethics stories because of a brief stint she’d had working at her dream job: a mission-driven tech company, at which, she told me, the founder and CEO was ousted by the board within months of Hao’s arrival, “because it was too mission driven and wasn’t making any profit.”

“That was a pretty big shakeup for me,” Hao said, “in realizing I don’t think I’m cut out to work in the private sector, because I am a very mission-driven person. It is not palatable for me to be working at a place that has to scale down their ambition or pivot their mission because of financial reasons.”

Hao’s comments got me thinking about the larger systems in which all of us who live and work in technology’s orbit seem to be trapped. We want to do good, but we also want to live well. Few of us imagine ourselves among the class that ought to intentionally step backward socio-economically so others might step forward. After all, there are tech executives who make $400,000 a year but still can’t afford their mortgages in Silicon Valley: should the revolution begin with them? But if not, just who does need to take personal responsibility for participating in oppressive systems of privilege?

Whatever the answers, Hao strikes me as sincere, smart, and well-intentioned, and I’m impressed she gravitated away from the moral compromise of the for-profit sector to her current role as a journalist, toward “mission-driven” work. But now that I’m not sitting with her as her chaplain but as a fellow journalist, should I dig deeper, question harder?

The MIT Technology Review, after all, might have something to gain from presenting a certain kind of tech coverage. There are advertising dollars and conference registration fees at stake, and it’s not difficult to imagine how these things might incentivize coverage that pulls punches. Attendees at a conference like EmTech Next might want to be challenged intellectually to think about ethics. But do they really want to hear, for two days straight, about perspectives that would cause them to question not only their own money-making abilities but also their moral character?

Granted, these are the risks one runs in trusting the coverage of virtually any issue at virtually any mass-media publication. And particularly after the despicable and anti-American treatment to which Donald Trump has subjected the press these past few years, I tend to give hard-working journalists such as Hao the benefit of the doubt. That said, how many costly errors in judgment at tech companies could have been avoided if tech coverage had been less fawning?

And one need only look down the road a few … actually not even a few steps from where Hao and I are sitting, to realize that sometimes even the most promising-seeming efforts to write about and study technology ethically are deeply flawed at best.

The exterior of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab/ (Photo by Craig F. Walker/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

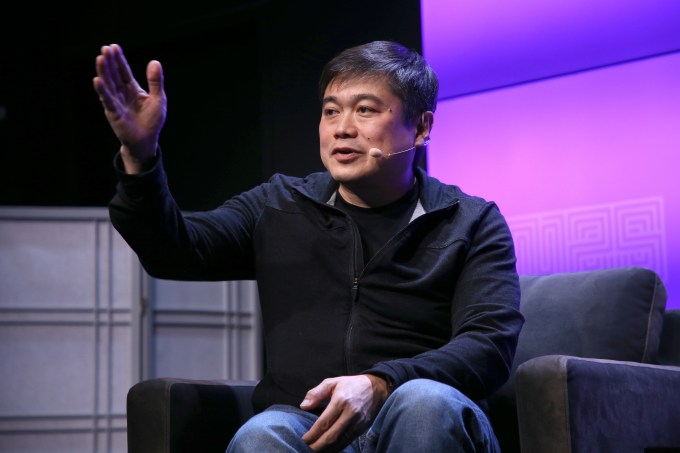

After all, the gleaming Media Lab building, in which the conference took place, was under the direction of Joi Ito, a tech ethicist so legendary that when Barack Obama took the reins of an issue of Wired magazine as a guest editor in 2016 — as the sitting United States President — he asked to personally interview Ito about the future of artificial intelligence. Just two months or so after Hao and I sat there, news broke that Ito had cultivated a longtime relationship with none other than Jeffrey Epstein (no fucking relation, thank you), the notorious child molester and a ubiquitous figure in certain elite science, tech, and writing circles.

Joi Ito (Photo by Phillip Faraone/Getty Images for WIRED25)

Not only did Ito take at least half a million dollars in donations from Epstein against the objections (and ultimately the resignations) of star Media Lab faculty, he repeatedly visited Epstein’s homes. Epstein even invested over a million dollars in funds and companies Ito personally supported. “But forgiveness,” some friends and supporters of Ito’s might say. And on a personal, human level, I see their point. I’ve never met Ito; from what I’ve heard, I assume he’s a great guy in many ways. But he used his leadership role to closely associate with a convicted criminal and known serial sex trafficker of children, who, as one MIT student wrote, was part of “a global network of powerful individuals [who] have used their influence to secure their privilege at the expense of women’s bodies and lives.”

To Ito’s credit, he seems to have been devastated by the revelation of his fundraising choices (as he should be). But had the sources of tech funding been more scrutinized by the tech media earlier, would the entire situation have been less possible?

Maybe this entire saga of Jeffrey Epstein and the Media Lab seems less than fully related to the broader point I’m trying to make about how the “future of work,” as a genre of academic discussion, refers to a vicious cycle in which a few winners perpetually win at the expense of the rest of us losers, while casting themselves not as rich jerks but generous, thoughtful moral paragons. But that’s exactly what the Epstein story is about.

Consider, for example, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, whose mission statement (at least in one iteration) states that it is “Guided by the belief that every life has equal value,” and that it “works to help all people lead healthy, productive lives.” This sounds great in theory, but what does it even mean in practice? Who decides what it looks like for every life to have “equal value?”

That last rhetorical question probably sounds pretentiously philosophical, and maybe it is. But it also has a concrete, literal answer: notwithstanding the important contributions of others like his father and wife, at the end of the day, Bill Gates decides on the direction of the foundation founded on his twelve-figure net worth.

When we think of Gates deciding how to promote the equal value of all lives, we must absolutely picture him deciding, despite the almost literal army of philanthropy consultants he would have had available to advise him otherwise, to meet cozily and honestly quite creepily with Jeffrey Epstein in 2011, long after Epstein was a convicted felon for such crimes. Where was Gates’ respect, in deciding to indulge in those meetings, for the equality and value of the lives of the girls Epstein victimized? They were vulnerable CHILDREN, as journalist Xeni Jardin points out, and Gates either knew this or willfully barrelled past a phalanx of experts who would have informed him.

Bill Gates has, to this point, escaped most criticism for his bizarre actions because of the “social good” his foundation does. And so we allow individuals like him to hoard the resources necessary to do such grand-scale charitable work. We could tax them much more and redistribute the proceeds to poor and exploited people, which might well eliminate the need for their charity in the first place. But we don’t. Why? Largely because of the belief that people like Gates are super-geniuses, which Gates’ involvement with Epstein would seem to disprove.

Then there is MIT more broadly. The Institute’s mission statement is “to advance knowledge and educate students in science, technology, and other areas of scholarship that will best serve the nation and the world in the 21st century,” but of course, it has a long history of advancing the production of weapons of mass destruction and of serving the military-industrial complex. The university’s newly-announced Stephen A. Schwarzman College of Computing, set to be the first wing of MIT to require tech ethics coursework, is named after a donor who has close personal ties to Donald Trump, not to mention the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, and, say, opposition to affordable housing.

It’s all a maddening feedback loop, in other words.

We continually entrust “special” individuals like Gates and Ito and institutions like MIT and Harvard with building a better future for all. We justify that trust with the myth that only they can save us from plagues to come, and then we are shocked — shocked — that they continually make decisions that seem to prioritize a better present … for themselves. Rinse. Repeat.

Of course, MIT is ultimately just a collection of people with incentives and feedback loops of their own. It supports the doing of great good as well. This is just to say that we can never afford to blindly trust tech coverage, tech ethicists, tech ethics conferences, or even tech ethics journalists slash atheist chaplains like me. There is too much money at stake, to name only one potential motivator for moral betrayal.

All of us who choose to involve ourselves with these industries, in the name of a better future, should have to live with skepticism, and prove ourselves daily through our actions.

“Show me your budget, and then I’ll tell you what your values are.”

Charles Isbell via MIT Technology Review

“There’s an old joke about organizations,” says Charles Isbell, the dean of Georgia Tech’s College of Computing and a star on the next EmTech Next panel, called ‘Responding to the Changing Nature of Work.’ “Don’t tell me what your values are, show me your budget and then I’ll tell you what your values are. Because you spend money on the things that you care about.”

Isbell is evangelizing Georgia Tech’s online master’s program in computer science, which boasts approximately 9,000 students, an astronomical number in the context of CS, and the program also has a much higher percentage of students of color than is typical for the field. It’s the result of philosophical decisions made at the university to create an online CS master’s degree treated as completely equal to on-campus training and to admit every student who has the potential to earn a degree, rather than making any attempt at “exclusivity” by rejecting worthy candidates. Isbell projected that in the coming years all of this may lead to a situation in which up to one in eight of all people in the US who hold a graduate degree in CS will have earned it at Georgia Tech.

Tall, dapper, and with the voice and speaking style of an NPR host, Isbell draws a long line of question-askers in the hallway after his panel (including Gupta of course, and me as well). He can’t promise to even open all the emails people want to send him, so he tells those with particularly good questions to fill in the subject line with a reference to one of his favorite 80’s hip-hop records.

In a brief one-on-one interview after he finishes with his session and the line of additional questioners, I ask Isbell to explain how he and his colleagues so successfully managed to create an inclusive model of higher education in tech, when most of the trends elsewhere are in the direction of greater exclusivity. His response sums up much of what I wish the bright minds of the future of work were willing to make a bigger priority: “We have to move to a world where your prestige comes from how much better you make [your students]. That means, accept every person you believe can succeed, then help them to succeed. And that’s the difference between equality and equity.”

“Equality,” Isbell continues, “is treat everyone the same, [not knowing whether] good things will obtain. Equity is about taking people who can get from here to there and putting them in a situation [to] actually succeed … without equity, you’re never going to generate the number of people we need in order to be successful, even purely from a selfish, change the economy, make the workforce stronger [point of view.]”

Maybe what we really need are conferences on the future of equity. What if the extraordinary talent, creativity, discipline, and skill that has been poured into the creation and advancement of technology these past few decades were instead applied to helping all people on earth to obtain at least a decent, free, dignified quality of life? Would we all be stuck on the iPhone 1, or even the Model T?

Perhaps, but I have to imagine if seven billion people were well-fed, educated, and cared for enough to not have to worry constantly about their basic needs, they’d have reason to collaborate and capacity to innovate.

But now I’m philosophizing for sure. So I try to snap out of it by asking a concrete and focused follow-up question of my next interviewee, MIT Technology Review’s editor-in-chief Gideon Lichfield: does Lichfield see his publication’s role as bringing about the sort of equity Isbell is describing? Or is he content for his magazine to promote the toothless, status-quo “equality” of “opportunity” most tech leaders seem to have in mind when hawking “Big Ideas” like Universal Basic Income?

Gideon Lichfield via MIT Technology Review

Once I’ve finally pulled Lichfield aside for an in-conference private audience, I find myself straining to discuss my ideas without completely offending him. Maybe it’s his impeccably eclectic wardrobe: the European designer jacket with some sort of neon space-monster lapel pin reminds me of my childhood in New York City, trying unsuccessfully to keep up with the latest trends among kids who were either richer than me, or tougher, or both.

I don’t want to allow myself to be intimidated, but I also don’t want to sound naive about the business world he and I are both covering. And Lichfield is clearly no dummy about questions of justice and inequality; when he explains that a lot of people in his audience work at medium and large companies who have to think of the value of their investments and other “high-end decisions,” I can guess what might happen if he one day booked a conference speaker slate filled with nothing but Social Justice Warriors.

Still, I want to know how much responsibility he’s willing to take for his own role in creating a more just and equitable future of work. So I use my training as a chaplain, delivering a totally open-ended question, like we do when conducting what are called “psychosocial interviews” to figure out how a client thinks. Beyond all this talk of the future of work, I ask, “how will we know, in 20 or 30 years, that we’ve reached a better human future than the reality we have today?”

“Wow, this is tricky,” Lichfield responds. “I feel like this is a really controversial question.”

“It is,” I respond too quickly for anything but earnestness. “I’m asking you the most controversial question I can ask you.”

Lichfield eventually offers that if society’s “decision-making processes” were more accessible to poorer people, that would be a better future; because while “you could end up with disparities,” he says, “you will also end up with choice.” But does this fall short of the vision Isbell and his colleagues at Georgia Tech have expressed through their project of putting knowledge in the hands of far more people than can usually achieve it in our current system?

When I add my signature question, which I ask at the end of all of my TechCrunch interviews: “how optimistic are you about our shared human future?,” Lichfield gives me the most gloomy answer I’ve received in my over 40 interviews to date. “I’m not especially optimistic … In the very long term, you know, none of it matters. The species disappears. And I’m pretty pessimistic in the short term [as well.]”

After a brief disclaimer about how he might feel better about our prospects for the end of this century, we wrap up, and agree to chat again sometime. Yet I’m left with more ambivalence: Lichfield comes across to me as a likable guy who leads a smart and engaging publication and conference.

But how often do influential men (like me, too, at times!) use “likability” to deflect criticism, persuading you to trust their personalities instead of questioning their motives, not to mention their profits? Whether or not the point applies to Lichfield himself, it would certainly be a valid criticism of many rich executives and elite leaders who sponsor and attend conferences like this one, selling us (and themselves) on their virtue and goodness today even as they pave their own way toward even more global domination tomorrow.

The thing about ghosts is, it’s their job to haunt you

Mary Gray via MIT Technology Review

At the next big panel I attend, things turn dark. In a good way.

The session, entitled The Dark Side of On-Demand Work, is moderated by Hao, the AI reporter, and features Mary Gray, an anthropologist and tech researcher, and Prayag Narula, founder of the startup LeadGenius and one of the subjects of Gray’s book Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley from Building a New Global Underclass (co-authored with Siddharth Suri, a computer scientist).

“Gideon talked this morning about the best jobs and how to acquire more of them,” Hao says, quipping: “now we’ll talk about the worst jobs.”

The topic of the session is what Gray calls “on-demand platform knowledge work,” the kind of contract labor or “gig work” where the entire point is for the (now countless) people doing the labor to become invisible so as to make AI look more impressive than it currently is (not to mention so they remain in the sort of shadowy realm generally understood to be a lousy bargaining position for a living wage).

We have no exact headcount for contract labor in the U.S., but it represents most of the growth in our economy in recent years, and is expected to be a $25 billion industry by 2020.

If gig work is the future, how will workers build careers? “You don’t become an Uber driver, then a Senior Uber Driver, then an Uber Manager,” cracks Narula, who was invited to speak because his company, which he admits employs ghost workers to track down business leads for busy executives, strives to pay a living wage. In some socialist utopia off in another dimension, a Chris Rock-like comedian would crack another joke: founders talk like they should get a cookie for paying living wages, when it’s literally the least they could do.

Here in this dimension, however, living wages for ghost work are still a big deal, worthy of MIT Media Lab stages. Which is probably why Gray, whom Narula says is more “communistic” than himself, supports eliminating distinctions between full time employees and contractors, along the lines of California’s recently passed “AB5” worker law, sparking potential for a progressive gig economy revolution. Gray wants to create a “labor commons” across the country, helping people live sustainable lives; she calls her book Ghost Work “the business case” for why and how we should do it.

We love to tout AI as the future of innovation, but what if we’ve deceived ourselves, with a combination of ghost work, tax evasion, and the like, into believing our present and future societies are much more advanced than the reality?

“Not Enough Value”

Kendall Square via Tim Pierce/Wikipedia

Heading home from the conference, I’m about to get on the Red Line train at MIT’s Kendall Square station when my “Charlie Card” metro pass buzzes loudly on the card reader: “Not Enough Value.” I am so immersed in my thoughts about what technology is doing to our values, for a second I honestly read the error message as a statement about my worth as a human being.

That probably sounds like a dad joke. I love a good dad joke, but it’s not. I’ve been working for many years, in therapy and the clinical supervision I do for my work as a chaplain, on an idea that I, like a lot of smart and highly accomplished people, internalized as a kid: that my worth or value as a human being is determined not by who I am but by what I accomplish.

The great psychotherapist Alice Miller, in her book The Drama of the Gifted Child, explains that though our parents may have loved us and taken wonderful care of us in many ways, they may also have sent us the subtle message that we are only really lovable if we are great. “You’re so smart,” parents may constantly tell their young children. “Look at how you won,” we then start saying to them, practically by preschool.

Our comments are well-intentioned, but what they convey is clear. We are what we do. We’re worthwhile because we’re outstanding. Which means: God help us if we aren’t. Children might intrinsically value kindness, curiosity, or loving relationships, but all too often we become obsessed with proving how great we are.

This “gifted child” mentality produces industriousness, to be sure; call it The Official Psychopathology of the Protestant Work Ethic. Left unexamined though, it leads us to constantly try to demonstrate our worth by out-working people, out-earning them, and out-greating them. We rarely stop to simply connect with other normal human beings or to allow ourselves to experience vulnerability.

Though it’s hard to feel warmth toward others while stuck in this mindset, we do need to constantly convey it. Because “winners,” remember, aren’t allowed to be naked sociopaths. They aren’t content simply to dominate the capitalist game, now and forever — they have to show you how likable they are while doing so. They have to show how deserving they are of their special status by “doing good,” not just making good.

So we end up with a company like WeWork, the shared office space company and symbol of an unethical tech future. In its recently filed IPO, WeWork said workers were yearning for a “re-invention of work.” Renters at WeWork offices were not clients or customers, but “members,” while neighboring workers were not just colleagues, but part of a “community.” Or so said Adam Neumann, only months before his platinum parachute cash-out, to the tune of $1-2 billion dollars, put the company he founded in such poor financial position that it couldn’t even afford to pay severance to thousands of laid-off employees.

Maybe the contrast between Neumann’s ridiculously communal language and his seeming rank selfishness is an extreme case, but it’s also fairly typical. In the elite social circles known for intellectual discussions of “the future of work,” it’s commonplace to use fancy language to to look not just important but heroic, even as our “innovation” disrupts lives and harms communities.

“How are we doing?” “Not very well.” On loving thy neighbor as thyself

I’m running late to the conference the next morning; I took a little more time playing one of my toddler son Axel’s favorite games: “jumping the shark,” over our living room couch. When Axel was born, I stepped back from my former life as an achievement-obsessed workaholic and encouraged my wife to embrace her busy law career. And not just for its steadier income — I love being Axel’s daily presence, trying to change every single diaper; entertaining his friends when I drop him off at daycare; and holding him tightly in my arms on long daily walks, discussing each new object along our way.

Prayag Narula via MIT Technology Review

Arriving at the Media Lab, I find Narula, who promised before his panel the previous day to describe how startups like his struggle to even attract venture capitalists to human-centered projects these days. He tells me about his friend with a similar business model — ghost work — but who, unlike Narula, doesn’t mention the “human factor” at all in pitches to VCs. The friend, far more successful at such pitches, once confided: “What I pitched to them is, ‘Hey, we are doing this today using people, but it will get automated in the future. And then because we have all this data, we will be the ones automating it.'”

When Narula asked, “do you really believe this can be automated?” his friend responded, “that doesn’t matter.”

“Our economy punishes people that rely on people,” Narula explains. “The education system and thought leaders have created this cascade effect of technologists not taking the human aspect of technology seriously.” I linger too long thinking about his story; now I’m even later for the first morning panel.

As I shuffle into the session, a discussion on the ethics of automation moderated by MIT Technology Review editor David Rotman, Rotman asks, “How are we doing?”

“Not very well,” says Pramod Khargonekar, a distinguished professor of computer science at the University of California.

On the panel with Khargonekar is Susan Winterberg, a fellow at the Harvard Belfer Center’s Technology and Public Purpose Project. Winterberg tells the story of Flint, Michigan’s famous exploitation of its poor, mostly people-of-color citizens, whose water was poisoned while their government abandoned them. Over 70% of Americans live paycheck to paycheck, she then explains.

The Flint Water Plant tower. (Photo by Bill Pugliano/Getty Images)

The number manages to make me the angriest I’ve been at the conference thus far. What can you even call a society whose vast majority doubts the future of their own work, while a small, comfortable minority lives in an almost literally different country? We don’t think of apartheid as something that could happen here, but that’s essentially what took place in Flint between April 2014 and…? Actually, as of this year, an estimated 2,500 lead service lines are still in place.

Winterberg’s talk pivots promisingly, however, to the story of how Nokia executives, including a former Prime Minister of Nokia’s native Finland, worked dutifully and creatively to help their own soon-to-be-displaced workers.

Winterberg’s story, published with Harvard Business School professor Sandra Sucher in a series of HBS case studies, begins in Germany in 2008. Nokia had closed a mobile-phone assembly plant in Germany that year, despite its record profits. The plant was not “cost competitive,” executives explained, with similar work being done in Eastern Europe or Asia.

Factory workers, politicians, and the German public were outraged, generating massive boycotts against Nokia. Unions organized people to ship their Nokia phones back to the company’s international headquarters in Finland. The anti-Nokia campaign cost €700 million in lost sales, Winterberg and Sucher found.

A few years later, after the smartphone revolution made it increasingly clear Nokia’s entire global phone manufacturing business would be decimated, company leadership chose not to abandon workers. Instead, it undertook a massive campaign to help employees cope with displacement, going so far as to stage career fairs and encourage other companies to hire its workers en masse. The campaign’s return on investment, according to the researchers’ analysis, was a thousand to one.

Photo by Josep Lago/AFP via Getty Images

“It’s their values, and it came from the very top of the company,” Winterberg tells me after her panel. “It came from the chairman of the board basically saying, ‘Find a way to do this that treats people with respect, that’s compatible with our values and will help us achieve the transformation we want to achieve, and report back.’”

Listening to her, I can’t help but wonder aloud: was Nokia able to model such solidarity (albeit only after failing in Germany three years earlier) thanks primarily to their roots in a homogenous and affluent society, where it’s a lot easier for management to identify with labor? “Love thy neighbor as thyself,” after all, has since Biblical times generally seemed to work out a lot better when racism and other forms of bigotry were not in play.

But, Winterberg reminds me, Nokia’s magnanimous response was also a global one. They had factories in China, the United States, and other far-flung locations, applying their “bridge program” basically universally. So I ask instead about her own background. From the Cincinnati area, she went to the University of Cincinnati as an undergraduate. There, she was deeply influenced by a field trip to urban Detroit, the degraded state of which made Winterberg want to know, “how could something like this happen?”

Moving on to a Masters in Urban Planning, then work as a researcher at Harvard, Winterberg came to understand the failures of the American Midwest in terms of a kind of unintentionally toxic coastal and economic elitism that has helped Donald Trump. “If you’re living in a small town and don’t have great tech skills,” she tells me, “your future is very dim. [My] presentation is designed to bring you to the experience of the more average person going through this and not just revert to your own experience where [mass layoffs are] basically just a bonus and an inconvenience for a couple of weeks. For most people, this is devastating and a lifelong change.”

Not everyone, in other words, can afford to view the future of work like a game, or from the relatively detached perspective of the typical attendee of a tech conference. And as Winterberg continued about Trump and right-wing populism more broadly, “He understands that from a political point of view. He’s been able to use that. We see that with politicians taking right-wing, populist stances across Europe. Brexit was a couple months before our elections here happened. It was the same thing.”

We’re all implicated, this makes me think. Not too many managers and executives intended to drive middle America into the arms of a Donald Trump. Certainly the centrist economic advisors in the Obama administration didn’t.

But we are all part of a system in which it is just too easy for people of means and privilege to glide along obliviously. It will take enormous, proactive, non-obvious action on our own part to avert disaster. But we’re stuck, deep in denial.

So I leave my conversation with Winterberg feeling sad: for our collective ignorance, and for the rarity of hopeful examples like 2011 Nokia.

To be fair

I find myself recharging as I talk, next, with Walter Erike. Erike, a mid-career independent management consultant also pursuing his MBA at Cornell’s Johnson School of Business, traveled from Philadelphia to attend EmTech Next, hoping to gain insights to inform his consulting business.

Erike, a Black man who spent much of his childhood in Harlem, is somewhat self-conscious about being a visible minority at the conference. But he’s also a dynamo of optimism and positivity.

“I don’t want to pile on MIT,” Erike tells me when I ask him how a conference like this, with a heavily white crowd, could be more relevant to other Black people in tech and related fields. “Because I don’t think it would be fair. But perhaps it would help if they were to reach out to the Urban League, reach out to the National Black MBA, reach out to the Consortium, reach out to NAAP, which is a national organization of Asians, to get more ethnic diversity in the room.”

Not inclined to linger on racial divides, Erike then steers the conversation to the idea of geographic diversity, echoing Winterberg’s concerns about the loss of manufacturing jobs in midwestern America. “If I hear many of the companies in the room, and if I consider where their headquarters are, we’re very West Coast, Silicon Valley focused, and New York, finance focused,” he notices. “There are a lot of really intelligent, motivated Americans living in the center, the Midwest, the breadbasket of America. From what I’ve heard and seen, they’re not represented.”

(My complete conversation with Walter, one of my favorite of the 40+ tech ethics interviews I’ve done for TechCrunch thus far, can be found here.)

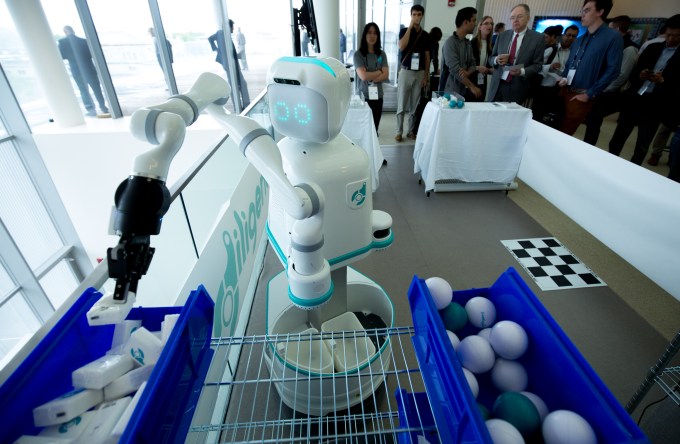

Next I talk with Andrea Thomaz, CEO and Co-Founder of Diligent Robotics. Diligent’s signature invention, a robot prototype named Moxi, is roaming outside of the presentation room. Slightly resembling the maid Rosie the Robot in “The Jetsons,” Moxi is a person-sized presence designed to assist overworked hospital staff. Moxi’s typical day, Thomaz tells me, would be spent trailing doctors and nurses responsible for training it how and when to fetch medicines and other necessary supplies, so they can spend more time with patients.

‘Moxi’ of Diligent Robotics via MIT Technology Review

Thomaz’s product, in other words, may be just the sort of thing to force the cynical critic of AI and machine learning to throw up his or her hands and admit, “you got me.” Who is Moxi hurting? How is it not at least one small part of the solution to real human problems? And then there is Thomaz’s background as a relatively young woman CEO and founder in robotics, with a PhD from the MIT Media Lab and experience teaching at public schools; God knows we need more stories like hers. Like Erike, Narula, Gupta and others, she impresses me as sincere, smart, dedicated to her craft, and determined to pursue it ethically.

Maybe there’s a way towards technological advancement alongside true human decency. Maybe all is not lost yet?

Is ‘Get Hooked’ the Answer?

It’s time to shut the conference down: organizers are peeling “EmTech” logo decals off the walls, but I’m not ready to leave the Media Lab — I need a place to collect my thoughts. Will the work of the future bring ever-ballooning inequality under the guise of what is ultimately the slick, self-serving “philanthropy” of Billionaire Humanism and Winners Take All? Or will the good people I’ve met here at this conference prove not only to be exceptional, but the ethical and inspirational rule?

Bewildered, I begin to wander home. Uber or Lyft are the most efficient way to get from MIT to my house, but I’ve been researching and writing about the ways in which ridesharing is morally compromised. That’s out, given my current mood.

Even a train feels too fast, too claustrophobic, too … technological. So I walk the hour-long route, first through the sleek, monolithic beauty of MIT’s Kendall Square (“the most innovative square mile in the world”) and then through a sleepy industrial neighborhood of tow trucks, a defunct-seeming rail yard, and a multiethnic, working-class population (an area about to be transformed, to the tune of billions of investment dollars, by a coming extension of the Boston metro Green Line train).

Finally, I arrive at Bow Market, a crown jewel of my current home city of Somerville’s ambitious plans for sustainable modernization.

Bow Market opened in the spring of 2018 as a former storage facility turned semicircular courtyard for more than 30 local, independent restaurants, shops, galleries, and even a comedy club. The businesses are mostly women-owned, and the Market’s developers are proud of their nearly 30% minority and 20% non-cisgender owners, too. A quick walk through and you’ll find everything from hand-carved wooden pins of James Baldwin and Zora Neale Hurston to vintage heavy metal t-shirts and motorcycle gear, to grilled pickle pizza and a chocolate mousse in a small chocolate waffle cone that is literally the best thing I have eaten in my entire life.

I go in to Get Hooked, a Bow Market fish shop run by Jason Tucker, a stocky, six-foot-something, grey-bearded New England fisherman with a Bahstan accent. Tucker has a humble, folksy manner and a knack for delicate dishes of lightly marinated blueberry-sized cubes of melt-in-your mouth fish, alongside field greens, citrus, kosher sea salt, and brown rice.

He and his business partner Jimmy Rider started this shop, then partnered with Matt Baumann, a former “money lawyah,” in Jason’s gruff expression, who changed directions several years ago for a career smoking fish. From May to October, Tucker is out on Cape Cod Bay chasing striped bass, mackerel, bluefish, and tuna. And this particular summer Wednesday night, he’s here making $14 bowls for people like me. I take my tuna ceviche in compostable cardboard to a metal table adorned only by a small blue jar. Over the course of my meal, the jar lights up as a sparkly, solar-powered, dark-activated lantern.

The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson, in a 2015 cover story, “A World Without Work,” examined growing research on America’s likely steep decline in jobs in the coming decades. Thompson tells, for example, the story of a 54-year-old writer, grandmother, and former university literature teacher in the post-industrial city of Youngstown, OH, who took a part-time job as a hostess at a cafe, just to stay afloat.

But he also discusses different possibilities, including one scenario he calls “The Artisan’s revenge”: Harvard economist Lawrence Katz’s vision of a world in which 3D printing machines create much of our basic infrastructure, leaving room for a new artisanal economy “geared around self-expression, where people do artistic things with their time.”

Is 3D printing the future of work? Photo by Manjunath Kiran/AFP via Getty Images

“In other words,” Thompson wrote, the future of work “would be a future not of consumption but of creativity, as technology returns the tools of the assembly line to individuals, democratizing the means of mass production.”

So is Get Hooked, and the entire Bow Market in which it sits, the answer? Local working people, applying their crafts with extraordinary artistry, at prices high enough to support a living wage but accessible enough to at least be a very occasional treat for other working-class people, while helping build a diverse, multiethnic, gender nonbinary, social-justice community where an entire city can come together to laugh, to celebrate, to eat, and to ponder important issues?

Or will it ultimately only be people like me, who have the enormous luck and fortune to afford homes in Somerville (current median single family house price: $799,000 and rising) and plunk down $20-plus for a light meal, who are able to enjoy this kind of “artisanal” and “community” experience “sustainably”? Am I doubling down on being part of the problem right now? I don’t know, but I can tell you which way I’m rooting, because that smoked fish is good.

Will the future of work be ethical?

I’m happy to admit I don’t know exactly what the future of work ought to be. I am developing my own ever-evolving understanding of what true human dignity and flourishing mean and what a healthier, less dystopian future might look like; I hope to elaborate on it later, including in a book I’ve recently begun to write.

For now, I can say a better future will demand emotional awareness and vulnerable courage from those currently in positions of power and privilege. We have to recognize that though we may not have caused these problems, we are responsible for them. Such a recognition is bound to be painful and confusing. It’s okay — wise, in fact — to not be able to face such a reality alone.

This is why I wasn’t entirely kidding when I wrote that the entire tech industry could use a Chief Social Work Officer to help us cope with constant feelings of anxiety and inadequacy. Maybe more women in leadership across the board(s) will help too, as I’ve discussed with feminist tech philosopher Moira Wiegel.

Wiegel argues that the internet has feminized our entire culture, and we need to embrace the positive aspects of such a change. If we do, maybe we can replace some of our tendency to grasp for power with the visceral joy of being on what tech critic and ethicist Douglas Rushkoff calls “Team Human.”

Meanwhile, however, we don’t need a perfect prophecy for a better future to know that much of what passes for discussion of “the future of work” isn’t it. It’s obvious such discussions exclude and, in effect, dismiss the majority of humans who will have to actually live through that future.

It should also be obvious by now: if it takes a corrosively unequal future of work to maintain profit margins, maybe there needs to be a lot less profit.

I can hear the VC philosopher protest: “who decides how to re-distribute my money?” So, yes, of course, any re-distributive efforts to remake the future of human labor will be complex, flawed, and require enormously vigorous debate.

But the main point I’m trying to make is actually simple. You can have a massively unequal economy, or you can have an ethical one. But please don’t continue to insult us by claiming we can all have both.

If you want to be on the side of an even somewhat status quo distribution of work by those who “create” it to those who are supposedly lucky enough to receive it, you’re free to hold such a position. But then don’t be surprised when increasing millions (billions?) of people try to hold you and your position accountable by denying your efforts to portray yourself as a philanthropist and humanist who only has our best interests at heart.

Though you won’t hear much about it in the various reports and conferences, maybe the future of work is a lot more work stoppage. More protest movements, like the ones that brought 11 deaths and thousands of arrests in Chile, or the ones that mobilized nearly a million people into the streets of Hong Kong, also causing a dozen or more deaths. Maybe the future of work clogs American streets, making it harder to recruit top talent, bringing down IPO valuations. Maybe it gives way to more unions, across almost every kind of industry and sector. Maybe more Cooperatives. Maybe Neo-Luddism. Probably fewer billionaires by far. And a Green New Deal. In short, the future of work will quite possibly be conducted on a very different political and moral playing field than that of today.

Is this the only possible ethical vision? No, but the onus is on those currently in power to prove to the rest of us that another worthwhile possibility exists.

“Will the Future of Work be Ethical?” I ask Mary Gray in our post-conference interview, explaining that the question would likely be the title of this essay. “I love that ,” Gray responds. Philosophers answer questions with more questions; anthropologists compliment your questions and then go back to thinking about their own.

“But will it be?”

“I would say it can be,” Gray allows, “if we move towards imagining valuing the collective contributions of people and stop looking for a future of work that looks like the past. It’s not going to look like a better version of the past.”